I often studied stocks like I would study people; after a while their reactions to certain circumstances become more predictable. – Jesse Livermore

Preface

This is the second in a series of posts regarding The Emotionally Intelligent Investor by Ravee Mehta. This post will deal with empathy.

Most Important Things:

“The ability to be in the shoes of other investors and feel what they are feeling is an indispensable weapon in the investor’s armory.”

A price chart can reveal significant insights into the emotions and thoughts of current security holders.

Developing social awareness can provide a competitive advantage, whether you’re evaluating management during presentations or analyzing an annual report.

Social awareness, like self-awareness, has been shown to improve with effort.

Contents

Emotional Edge

Mere Astrology?

Signal

People-watching

Emotional Edge

Having established the importance of self-awareness, Mehta goes on to discuss how empathy - placing oneself in the position of other market participants - is an indispensable weapon in one’s investing armory.

Alternatively pulled by both fear and greed, market participants often act in a manner that can, at times, be anticipated. This is where empathy comes in:

For example, in early 1990, [Paul Tudor] Jones empathized with the tremendous pressure Japanese fund managers were under to return at least 8% per year. While it may seem like an aggressive expectation in today’s market, the average Japanese household in 1990 had become accustomed to making at least 8% per year. Any manager who underperformed that hurdle rate ran the risk of losing his job. So when the market sold off 4% in January, the Japanese portfolio managers had a choice: they could keep their jobs and still make the 8% minimum return by reallocating aggressively into bonds or they could take a risk on trying to outperform by buying even more equities. By putting himself in the shoes of the average Japanese fund manager, Jones realized that most of them would not want to risk their jobs. Consequently, Jones correctly bet that the Japanese stock market would suffer a major correction.

Given the increasing capabilities of machines to perform quantitative analysis, Mehta believes that consciously employing empathy can facilitate a real edge in the market:

Not utilizing empathy while investing is a terrible waste of mental resources. Nevertheless, most text books on investing spend almost no time on it. Instead, they focus almost entirely on quantifiable items that are easy to analyze. The problem with things that are easy to quantify and analyze is that computers can generally do that much better and quicker than humans. Consequently, the investor can have difficulty ever gaining a competitive advantage by just employing traditional security analysis. The great thing about empathy is that we are all born with it. Infants have been shown to imitate facial expressions of those in front of them almost immediately after birth. The easiest way to gain an investing edge by employing our God-given capacity to empathize is to simply ask yourself what others in the marketplace may be feeling. You should try to understand what the current shareholders and potential buyers of a particular security are thinking before you make any investment decision.

Mehta also cites research that distinguishes between cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, and empathetic concern. I’m not convinced such a fine-grained distinction is required to benefit from the broader point of bringing the following to mind before deciding to buy, sell, or hold:

What does the current shareholder base look like? Is it mostly comprised of value investors who usually bet against the current momentum and take a longer term perspective, or growth and shorter term investors who typically sell after poor results?

Is there a high short interest?

Does management own a large percentage?

What are the longer term shareholders thinking and feeling? What are the shareholders who recently bought the stock thinking and feeling? What is the potential buyer of the stock thinking and feeling?

What is the potential short seller of the stock thinking and feeling? If the stock has a high short interest, what are those who are already short the stock thinking and feeling?

What is management thinking and feeling?

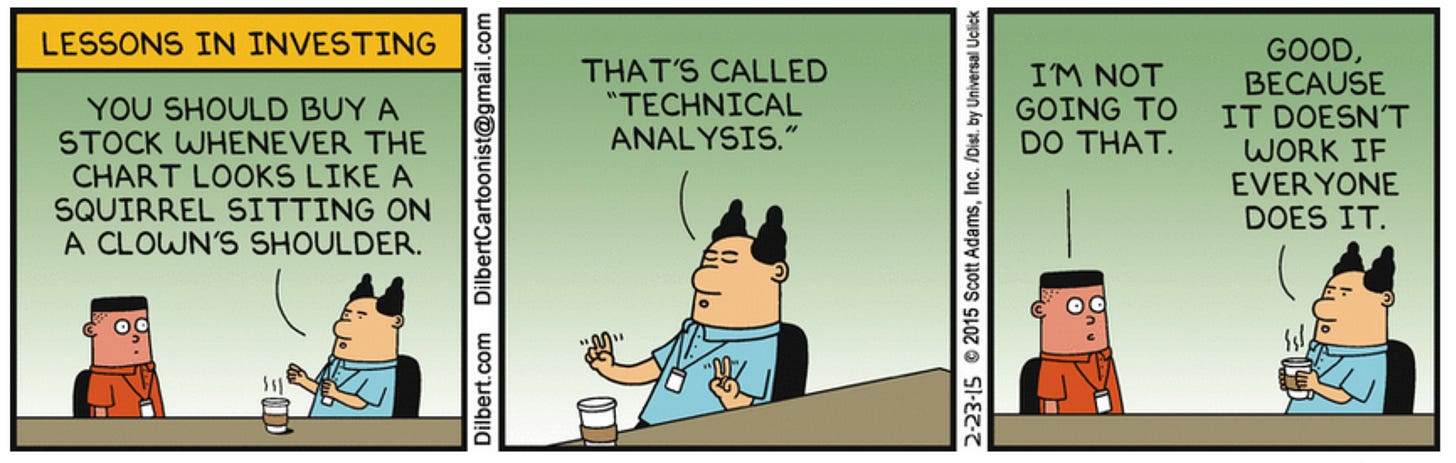

Mere Astrology?

Unexpectedly, Mehta goes on to discuss how empathy provides a rational basis underpinning the use of technical analysis:

Technical analysis works because it takes account of investor psychology. A chart can tell you a tremendous amount about what the current shareholders of a security may be feeling.

He then recounts how his early scepticism gradually gave way to acceptance:

When I started investing in the public markets, I thought that analyzing charts was a complete waste of time. At Wharton, I learned about how a company’s market valuation was theoretically based on the present value of the free cash flow it would generate for shareholders over time. We learned almost nothing about how a stock’s historical pattern can be indicative of future performance. I tended to view stock market technicians as almost like astrologers or witch doctors…It all seemed to make no sense. I originally dismissed trying to learn anything about reading charts, but that started to change. I read books like Market Wizards and saw that many of the greatest investors actually heavily relied on technical analysis. I also started noticing that some of the best known technicians that worked at sell-side brokerage firms appeared to be right much more often than not. They seemed to be especially prescient in calling turns in the overall market. For example, many technicians turned bearish in 2000 and in 2007 well before it became clear the economy’s fundamentals were significantly weakening.

Now amongst the converted, Mehta provides an example to illustrate its efficacy:

The chart above is of Apple (AAPL) stock from 2001 to 2003. It is an example of a chart that formed a resistance level. The stock spent a fair amount of 2001 and the first half of 2002 trading in a range from about $11 to $13. During the summer of 2002, Apple’s stock then suddenly declined. Let’s put ourselves in the shoes of an average shareholder in early 2003 when the stock was at $7. These shareholders were sitting on paper losses. Many acquired the stock over the last couple of years at prices that were higher. They were hoping for a bounce in the stock, so that they could sell and potentially have a break-even result or a slight gain. That way, they could avoid the shame that comes from being wrong. Since many bought slightly under $13 - that would be about the same price they would sell. This intention for many shareholders to sell at a certain price creates a resistance level. When the stock moved up towards the end of 2003, many of these shareholders unloaded their positions and the stock failed to get past $13 again. The more time a stock spends churning near the resistance level, the stronger the level tends to be. This is because new shareholders have an average cost basis near resistance. Therefore, duration and trading volume near resistance impacts how strong the level is.

Doubtlessly there will be those who remain unconvinced.

Signal

Technical excursions notwithstanding, you may feel that Mehta is on firmer footing when providing examples of how being socially aware can help when assessing a company’s management team:

Familiarity with a company’s incentive structure and with how its management historically reacts to questions can help with generating an investing edge using social awareness. For example, I once sat in a presentation by the CEO of an enterprise software company in which I was already invested. The Company had been performing poorly, so I had been using a value investing approach. The stock was trading at a very low valuation. I thought it was well below intrinsic value, especially if sales could start growing again. The presentation was made close to the end of the company’s quarter. There were probably 200 people in the audience and it was webcasted, so anyone could listen in. The company had recently had recently overhauled most of its management and when asked by an audience member about the new team, the CEO singled out the new VP of sales as someone he thought was “fitting in nicely”. I immediately felt even more confident in my investment. The fact that the CEO talked positively about the new VP of sales so close to the end of the quarter told me that the business was most probably performing well.

Conversely, Mehta provides some helpful pointers as to when the alarm bells should be ringing:

Another general rule of thumb is that when companies are doing poorly, you want to hear management increasingly talking about the short term. Steve Jobs, who was one of the best visionary CEOs of all time, did this when he took back the CEO job at Apple. Jobs focused on getting the company’s cost structure in line and secured a desperately needed investment from Microsoft. As business improved, his communication and focus gradually shifted towards the longer term vision for Apple. When a company misses quarterly expectations, but maintains or even raises longer term growth targets, alarm bells should ring in your head as an investor.

Moreover, the actual words used can be a vital clue:

Use of technical language and buzzwords that avoid answering the question. For example, on RIMM’s quarterly conference call in June 2009, Co-CEO Jim Balsillie was asked about why new subscriber growth from business customers was not doing better. Balsillie responded by saying, “I think what is going on with B2B is much more of an architectural shift. I mean that is why MVS is so powerful, in that the new MVS version is about making it a true synchronized PBX, and the SAP stuff is very important, because that is a native services environment. And then all the Wi-Fi for the FMC, and then the BES 5.0 is just getting out…” He went on and on spewing out technical jargon. RIMM’s stock declined over 80% in the 2 years following that earnings call.

People-watching

Thereafter, Mehta provides a reminder as to why social awareness is likely to become even more valuable:

Like self-awareness, social awareness has been shown to improve with effort. Nevertheless, business schools spend very little time helping students apply social awareness to investing. They primarily teach traditional security analysis. Business schools teach things like how to develop financial forecasts and how to conduct industry analysis. While fundamental security analysis is very important, it is increasingly being commoditized. Thousands of business school graduates, armed with this skill, enter into the investment management industry every year. Moreover, computers are constantly making the analysis easier to do. Financial analysts and business school students should take note that an investment is only attractive when most other potential buyers in the market underestimate its merits. Those who are most socially aware can best judge why others are creating a buying opportunity for you, and what needs to change to influence others to buy after you.

Concluding with some advice as to how one can go about refining the skill for oneself:

Next time you sit in a café or on a park bench, do a little “people watching” and try to think about what others may be feeling given their facial expressions. These exercises may sound corny, but researchers have shown them to be highly effective in raising social awareness. Traveling to different places and reading literature have also been shown to improve social awareness. When you put yourself into a foreign environment, you are forced to understand different perspectives. What may seem taboo to you may be quite normal to others. This can compel you to understand how certain things could be possible.

Note: I hope you’ve enjoyed Parts I and II. Part III will cover intuition.