You need a certain amount of intelligence, but it’s wasted over a certain level. After that it’s more about intuition. – Stanley Druckenmiller

Most traders who have not found their niche have never played with the markets. They haven’t tried to trade different styles, different instruments, and different time frames…Elite performers never stop playing. Artists sketch; athletes play in scrimmages; actors improvise. Play is a means of self-discovery. - Brett Steenbarger

Preface

Ravee Mehta is the Managing Director of Nishkama Capital and the author of one of the best books on investing I’ve come across, The Emotionally Intelligent Investor.

Despite being published over a decade ago, the book isn’t as widely known as it deserves to be; which is actually a good thing, because I’m certain that applying even a portion of the lessons it contains will help you develop a real edge in your approach to the market.

My aim in this series of posts is to give you some of the highlights from my own reading, but you should absolutely buy, read, and reflect upon the book for yourself.

Most Important Things:

Contrary to popular opinion, Mehta convincingly demonstrates that the touchy-feely stuff (self-awareness, empathy, and intuition) can be marshaled and combined with stone-cold, dispassionate analysis to make more profitable investment decisions.

This post will deal with self-awareness; empathy and intuition will be dealt with in subsequent posts.

Contents

Kirk or Spock?

Don’t play like Shaq

Style

Bridge

Kirk or Spock?

Mehta begins with a pretty arresting question:

Kirk or Spock? Which Star Trek character would have been the better investor? According to most investing text books, the answer is easy. It would have been Spock. He was able to block out his emotions and make purely rational decisions.

On first pass, this certainly sounds right, and echoes what Buffett and Munger have been known to espouse. Certainly, their acolytes are famous for attempting to expunge the merest trace of subjectivity from their cognitive processes, all the while seeking sanctuary in the near-hallowed edifices of ever more elaborate ‘mental models’.

Yet, Mehta isn’t convinced:

The world’s legendary money managers use their feelings. Instead of suppressing emotion, they actively sense what others in the market are thinking. They also employ gut instincts when making decisions. How is it possible that these great money managers complement rational thinking with some of their feelings to make better investment choices?

This is the essential question, and in just shy of 200 pages, Mehta provides an elegant framework for thinking about how to do just that. In particular, he emphasizes the importance of harnessing self-awareness, empathy, and intuition, to help augment one’s analytical approach to the market.

Don’t play like Shaq

That all sounds well and good in theory, but why not just avoid all this heavy emotional stuff, and emulate the GOAT? Surely, like everyone else on Twitter, that will keep my equity curve up constantly moving up and to the right?

Turns out, Mehta argues, imitation can be pretty hazardous to your investment returns:

Too many people try to emulate Warren Buffett even though they may have weaknesses, motivations and personality traits that are in conflict with his approach to investing. It would be like telling an aspiring basketball player who is only 5’8”to play like Shaquille O’Neal. The shorter player can still be great, but he needs to learn how to play in a different way. I used to work for George Soros, for example, and he would never have been successful if he used Buffett’s style. Contrary to popular opinion, there does not seem to be one type of personality that is superior. The master investor adopts an approach for making decisions that bests fits with whom he or she is. Given this fact, it is amazing how little time most people actually spend on self-reflection.

An approach based purely on emulation precludes a person from self-reflection; self-reflection is key to determining one’s strengths and weaknesses:

If you have a tendency to fall victim to a common trap, consider it a weakness. If you are not susceptible to a specific trap, consider this aspect of yourself to be a strong point. An investment strategy should minimize mistakes to which you may be most susceptible and it should capitalize on your strengths. It should fit with your personality and your motivation. Once an approach is established, it is important to stay consistent.

There are many investors who just work on self-awareness after they experience painful losses. This usually results in a cycle where losses lead to better discipline, which yields better returns, which is followed by hubris, laziness and lack of self-reflection. Inevitably, the cycle repeats after the resulting poor performance. The fallout is investment returns and a quality of life that is significantly worse than its potential.

Ultimately, long-term success is dependent on developing a unique, personal investment strategy; or style.

Style

My absolute favorite part of the book is Mehta’s discussion on aligning one’s personality and investment style:

There are generally two ways to invest: one can either be contrarian, betting against the crowd, or one can bet that more investors will join the crowd and the current trend will continue. Each approach requires a different skill set, and certain personality traits influence how successful one can be when using each style.

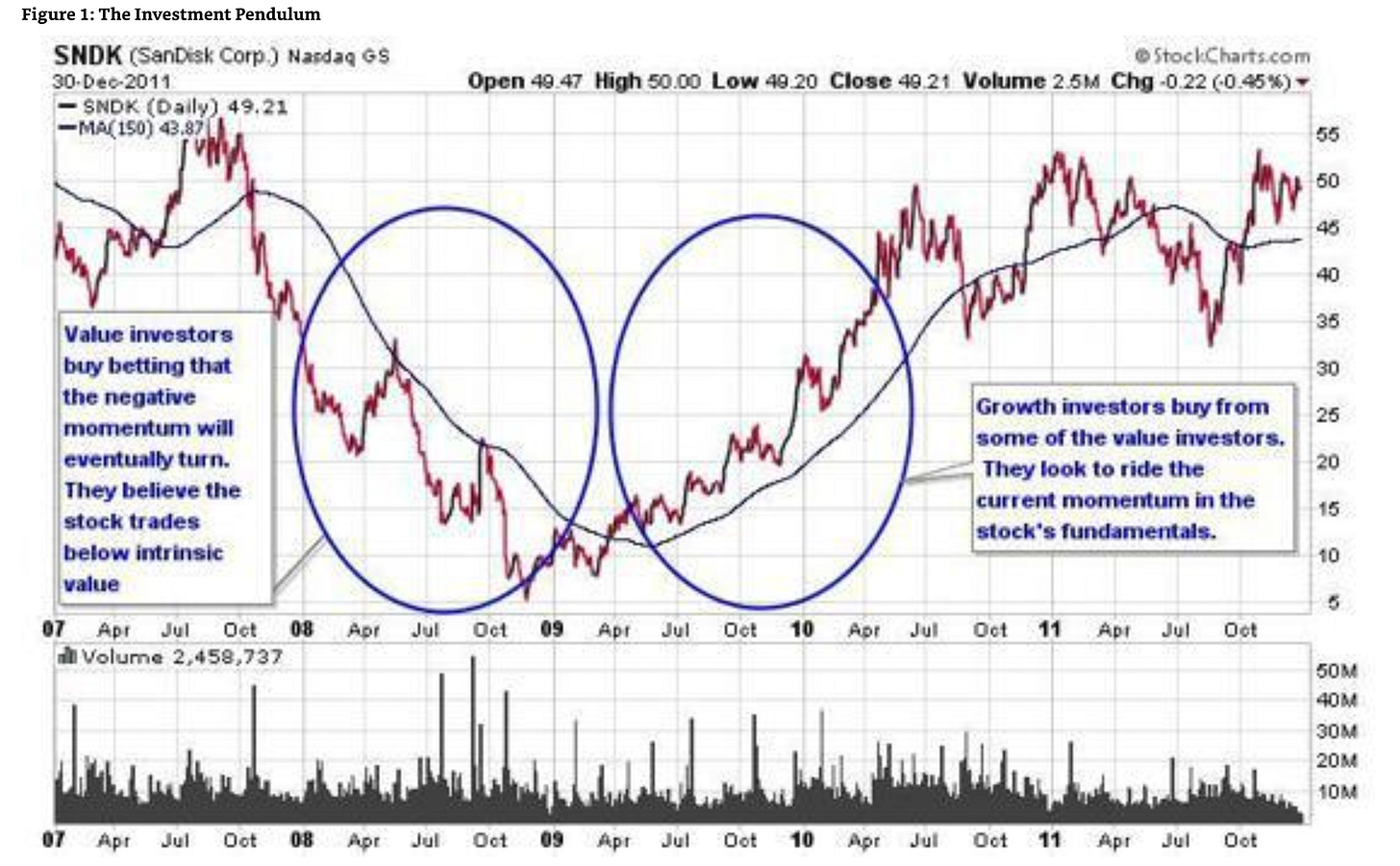

There are two general investing styles which take advantage of the swinging pendulum. Value investing involves trying to make money by guessing that the pendulum is near the end of its swing, all the way to the left or all the way to the right, and that it should eventually swing the other way. Growth or Momentum investing involves betting that the pendulum will continue in its current direction, left to right (let’s call it “bullish”) or right to left (let’s call it “bearish"). Success in each of these styles generally requires distinct personality traits and strengths. Within each of these approaches, an investment horizon can be either long term or short term. Investment horizon largely depends on what an individual finds most interesting about investing.

That line on investment time horizons is terrific and leads on to some of the most insightful passages from any investing book I’ve ever read (and I’ve read well over a hundred):

Problems often arise when people get confused with what style they should be using. For example, in early 1996, Julian Robertson, founder of Tiger Management, made a contrarian investment in US Airways. By the summer of 1998, the investment was up over 400% and worth $1.5 billion. The momentum on US Airways’ stock had clearly shifted yet Robertson still dealt with it in a “fighting the pendulum” frame of mind.

Robertson made the error of adopting the wrong approach after his investment had made significant gains, but often people make the same error at the outset of an investment:

Another common mistake is to mismatch investing style with the thesis at the time of the investment. For example, in 2006 all the US homebuilding stocks had more than a decade of strong gains…. Nevertheless, most of the analysts who recommended the securities primarily highlighted their relatively low price-to- earnings ratios. They used a value investing approach when they should have used a growth investing approach. Value investors commonly justify their investments using valuation support. However, valuation should only be a secondary factor for companies and industries that have been benefiting from favorable long term trends.

Reflecting on these events has led to Mehta formulating two distinct sets of rules:

My rules for investments that require a growth investing approach: When I invest in companies that have been beating Wall Street’s expectations and which clearly have momentum in their favor, I make it a rule to have a stop-loss. I also try to stay disciplined to not “dollar cost average” down with this type of investment. Instead, I may add as the position becomes a winner and I become more confident in my thesis. I am constantly on the lookout for a change in momentum.

My rules for investments that require a value investing approach: I initially ask myself why I want to bet against the current momentum. Do I think the security is trading at a significant discount to its intrinsic value? Or do I have a view of a timeframe for when the momentum will shift? Or both? If the primary reason I am involved in the investment is because I believe it is significantly undervalued, I do not use stop-losses. Instead, I determine a very low valuation and add to the position as it approaches this “no-brainer” price.

Finally, he adopts a useful heuristic for when to pass:

These rules of thumb are not perfect. However, I have found that when it is too difficult to determine which category a security should be in, time is usually better spent on other possible investments that are less difficult.

Bridge

The book highlights numerous different strategies to employ to develop one’s self-awareness, two favorites being the emphasis on confronting discomfort, alongside keeping a journal:

When we write about our emotions and how they impacted our decisions, we effectively create a bridge between our rational left brain and our more emotional and creative right brain. There are many approaches to keeping a journal. I write a short daily entry where I mainly focus on my mistakes and what I did well. I try to focus on my emotional state when prior decisions were made.

None of these are in any way revolutionary ideas, but what makes Mehta’s book unique is the incredible amount of thought and reflection he’s put into developing an investment approach that intelligently bridges both sense and sensibility.

Note: I hope you enjoyed Part I. Parts II and III will cover empathy and intuition, respectively.