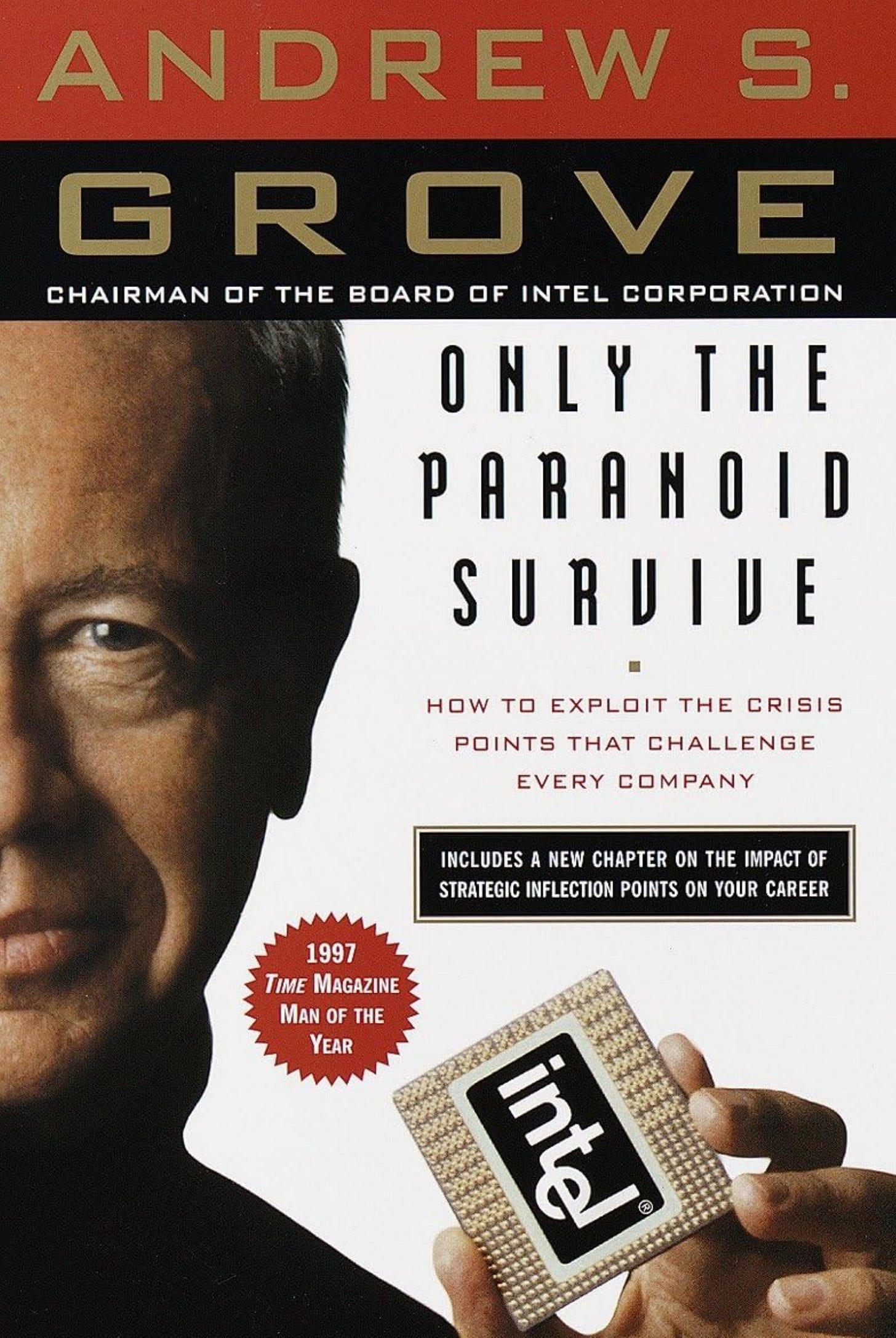

“Sooner or later, something fundamental in your business world will change.”

- Andrew S. Grove. Only the Paranoid Survive

Fall Guy

Pat Gelsinger's sudden departure from Intel marks more than just another CEO transition. His return to Intel in 2020 carried bold promisesan IDM 2.0 vision that would restore Intel's manufacturing leadership, build a viable foundry business, and use the company's own chip volume to fund that transformation. But these promises, however ambitious, came a decade too late.

Ben Thompson at Stratechery captured the fundamental problem:

Intel's products are irrelevant to the future; that's the fundamental foundry problem. If x86 still mattered, then Intel would be making enough money to fund its foundry efforts.

The roots of this irrelevance run deep. Intel's success was built on a paradigm where general-purpose CPU performance mattered above all else - a world that rewarded Intel's focus, scale, and integrated design and manufacturing approach. But technology markets are never static, and what once defined rational decision-making can quickly become a liability as the underlying logic of the market shifts.

Intel's board had initially supported Gelsinger's strategy. Now they've abandoned him, reverting to a product-first mindset that seems blind to the transformed computing landscape. While cloud and data center operators increasingly channel their compute spending into GPUs - often Nvidia's - a once all-powerful Intel suddenly looks ill-suited for tomorrow's computing demands. The problem isn't just that Intel missed mobile and AI - it's that Intel kept making decisions tuned to a reality that no longer exists.

Paradox

This is the paradox of incentives: Actors are rational to optimize for incentives as they exist today, yet irrational to believe these incentives will persist indefinitely. The very rationality that drives success in one paradigm can ensure failure in the next.

Intel bet on continuity instead of preparing for inevitable change. Its IDM 2.0 plan may have made sense had it been implemented a decade earlier, when Intel could still leverage its dominance to build a globally competitive foundry business. Coming late to the party, Intel found itself up against TSMC’s well-established ecosystem and a host of ARM-based designs that had already become the default in mobile and, increasingly, in data center acceleration. By the time Gelsinger tried to fix the company, the incentive structure that once seemed secure had long since evaporated.

For most of the past decade, Intel’s stock outperformed Nvidia’s. Why wouldn’t it? The market was focused on short-term signals and immediate returns. Nvidia’s investments in GPUs for AI seemed speculative, even wasteful, when viewed through a traditional CPU-centric lens. Yet Nvidia’s leadership, led by CEO Jensen Huang, understood that deep learning would transform computing.

As Tae Kim notes in The Nvidia Way:

Several of Jensen’s key lieutenants were against investing more in deep learning, in the belief that it was just a passing fad. But the CEO overruled them. ‘Deep learning is going to be really big,’ he said at an executive team meeting in 2013. ‘We should go all in on it.

That decision didn’t pay off immediately. It looked irrational within the existing paradigm. But now, the shift towards AI and specialized computing has validated Nvidia’s early investments. Only now, is Nvidia reaping massive rewards for betting on future incentives rather than the ones governing the present. Nvidia's story provides a perfect illustration of what building the future truly means: the willingness to underperform in the present because you're building for a paradigm others don't yet see. The market can discount only so far.

Paradigms

This pattern of shifting paradigms is a fundamental characteristic of technological progress. As the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn argued in the context of scientific revolutions, paradigms dominate thought and practice until anomalies accumulate, triggering a fundamental shift. The same logic applies to technology.

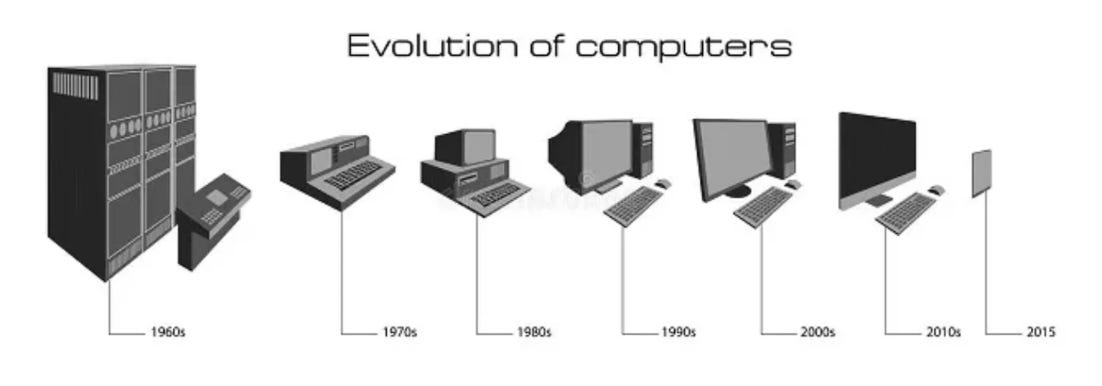

From mainframes to PCs, from PCs to mobile, and now from general-purpose CPUs to GPUs and AI accelerators, the underlying assumptions - and thus the incentives - are guaranteed to change. Everyone acknowledges these historical transitions, yet few behave as if another one is always on the horizon. Instead, companies act as though today’s incentive structures will last indefinitely. That’s the paradox: businesses know change is inevitable, yet the current incentive structure doesn’t reward preparations for future paradigms. Instead, markets often penalize investments that look “inefficient” or “unnecessary” within the current model. In fact, these transitions are happening faster than ever, making it more dangerous to cling to current advantages and more lucrative to adapt quickly.

Paranoia

Gelsinger’s departure isn’t just another boardroom drama. It’s a symbol of Intel’s inability to escape the incentive structures of the past. Rationality is always defined within a given paradigm - but paradigms always shift. As Intel clung to x86 and its IDM strategy long after the optimal moment had passed, it opened the door to TSMC.

Nvidia’s rise, in contrast, shows how betting on the next paradigm can yield outsized returns down the line. By the time the market aligns with new incentives, early movers are already positioned to dominate. The greatest strategic advantage isn’t just responding to current incentives - it’s anticipating tomorrow’s. As Nvidia have demonstrated, it’s not enough to be rational; you must be prepared - indeed, paranoid - about what comes next:

Yet Jensen didn’t want to allow any complacency to creep in, even in successful periods…In the technology industry, a single bad decision or product launch could be fatal. Nvidia had gotten lucky twice before, barely surviving the disasters of the NV1 and the NV2 before succeeding—with only months to spare—with the RIVA 128. That luck would not hold forever. But a good corporate culture would fortify the company against the dire consequences of most mistakes. And a mistake or downturn in the market was inevitable.

Still, as Dwight Diercks said, “It always felt like we were at zero. And the reason is that no matter how much money we had in the bank, Jensen could explain why we were going to be at zero with three things happening. He would say, ‘Let me tell you how. This could happen, this could happen, this could happen, and all that money goes to zero.’ ” Jeff Fisher pointed out that fear can be clarifying. Even today, although Nvidia is no longer thirty days away from going out of business, the company could easily be thirty days from starting down a path that will lead to its destruction. “You’re always trying to look around corners and see what we’re missing,” Fisher said.