For the gods perceive future things,

ordinary people things in the present,

but the wise perceive things about to happen.

- Philostratos, Life of Apollonios of Tyana

Disclaimer

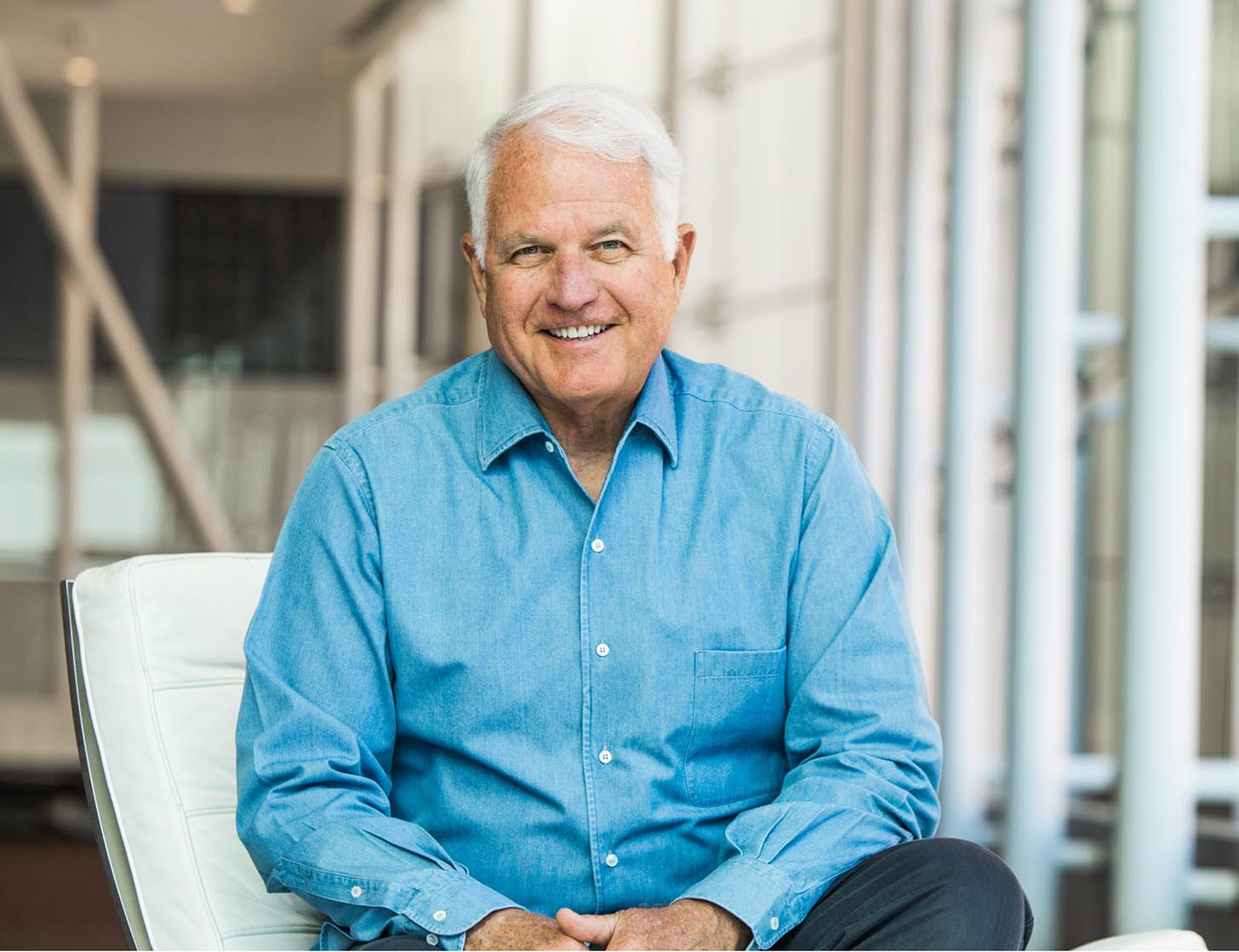

The following post is fashioned from the oral history provided by Jim Swartz, Founding Partner of Accel, to the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. Despite every attempt having been made to preserve his original intent, misinterpretations and errors are, of course, possible. Caveat lector.

Contents

“I don't think this is good for us.”

“I probably could be pretty good at this venture capital thing…”

“If you guys are so frickin’ smart, why are you here?”

“We didn’t want to put our names on the door.”

“It’s just evolved from there.”

“We approved nine companies yesterday. What were they again?”

“Let’s just liquidate…”

“Nobody knew how big it was going to be.”

“You’re trying to imagine the scenario.”

“Watch for change.”

1. “I don't think this is good for us.”

I took several digital computing courses at college in 1963. I thought digital computing was going to become really important in the future so I focused on that. It had a huge influence on where I decided to go to business school because I knew I didn't want to get an advanced degree in engineering, or at least I didn't think I did. So I began to think about business school and I came to the quick conclusion that Carnegie Mellon and MIT were really the centers of excellence for computer science and computer-based management science approach to business, which I felt was the future. So that's why I went to Carnegie Mellon.

I went through all of business school, never heard the word entrepreneurship, never heard the word venture capital, never heard of Silicon Valley. Of course, it probably wasn't coined yet, none of those were coined yet. Entrepreneurship was, but just in a very academic sense. So I had no window whatsoever into young companies, emerging companies. That just was not on the horizon. Everything revolved around what big company job you could get. Computer science and computers played a role because that defined the kind of job I would be moving into. The big challenge coming out of Carnegie Mellon— even today but certainly in that era— was getting yourself positioned away from being the computer scientist nerd and being a generalist. I mean, I was smart enough to know that I wanted to be a generalist and be positioned in general management, but I didn't want to get button-holed into being the resident computer jock. Consulting, corporate, big companies— that was the opportunity set.

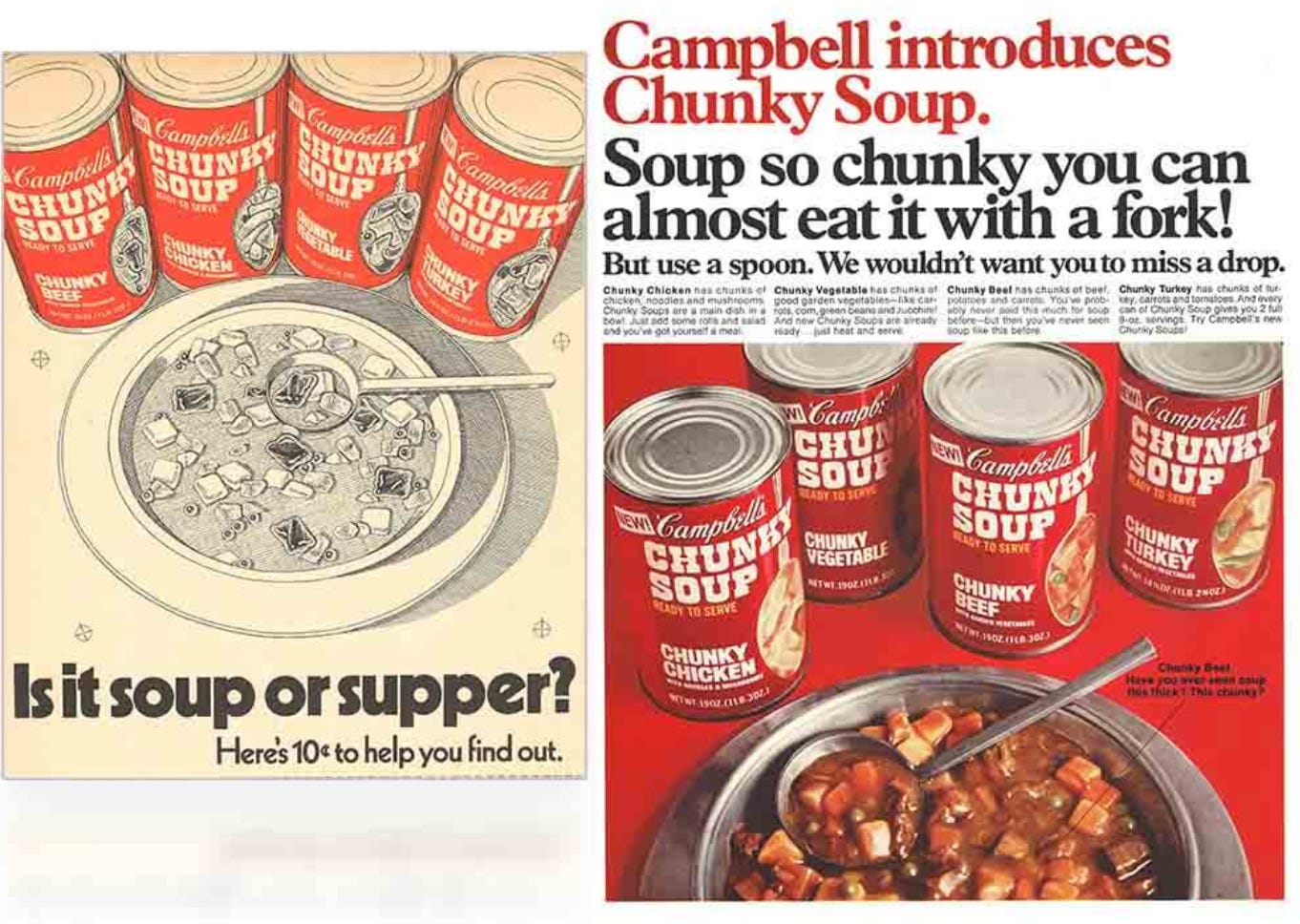

I chose a big company first because when I went to Carnegie Mellon I really loved manufacturing. I really thought I was going to stay in manufacturing and again, that was my exposure— living in a mill town, and I can vividly remember going to an interview at US Steel and walking out of there and thinking, “My God, these guys are dead. They're just toast. They don't get it. They don't understand.” Anyhow, I looked around. I wanted to get the highest position in manufacturing I could get to get a view of what life was like, so I took a job as assistant to the vice president of manufacturing at Campbell Soup Company. That was really eye-opening for me. I learned very rapidly that this was not what I wanted to be doing with my life, and manufacturing probably wasn't what I wanted to do with my life.

It was just the problem set that was being dealt with. It just wasn't an interesting problem set to me— the dimensions of what you could do, and the impact you could have. It was just so limited. I can remember writing papers around it. I'd read something in the Harvard Business Review or I'd read something that seemed really strategic, and I'd try to talk to them about it, and they'd look at me like I was crazy. And then, the military intervened. This was Vietnam. I was one of the lucky ones that got into the reserves. In those days, you had to either have political connections or money or some connection to—do that. When I graduated from Carnegie Mellon, I was drafted 1A. I was going to go as a PFC in the front lines and I knew I didn't want to do that. So I got myself qualified for Naval Officer Candidate School. I always wanted to fly. So I was ready to go be a Navy pilot. Then I met my future wife and she had a friend— you had to have some connections to get in the reserves— and it turned out in this particular reserve battalion that anybody who was leaving the organization, whose term was up, had a silver bullet. They could recommend a friend to go to the front of the line. He recommended me.

And so I went into the Army and eventually became a first lieutenant. I went off for six months. When I came back to the Campbell Soup Co, I told them, “I don't think this is good for us.” I had an offer from McKinsey, I had an offer from Cresap, McCormick & Paget, and an almost offer from Booz Allen Hamilton. I ended up choosing Cresap, and it was a good thing. I just felt there was more headroom at Cresap. As I looked around at the young guys and talked to them about it, there was an awful lot of headroom there and there didn't seem to be nearly as much headroom at McKinsey. So I went to Cresap, and I analyzed it right. But instead of retiring and turning the firm over to the younger guys, they sold it to Citibank. I was there for three years and then it was sold after I left. But I had a really good run there. The headroom was there. I had a lot of great assignments, was given a lot of responsibility, and it was a really important learning experience for me.

2. “I probably could be pretty good at this venture capital thing…”

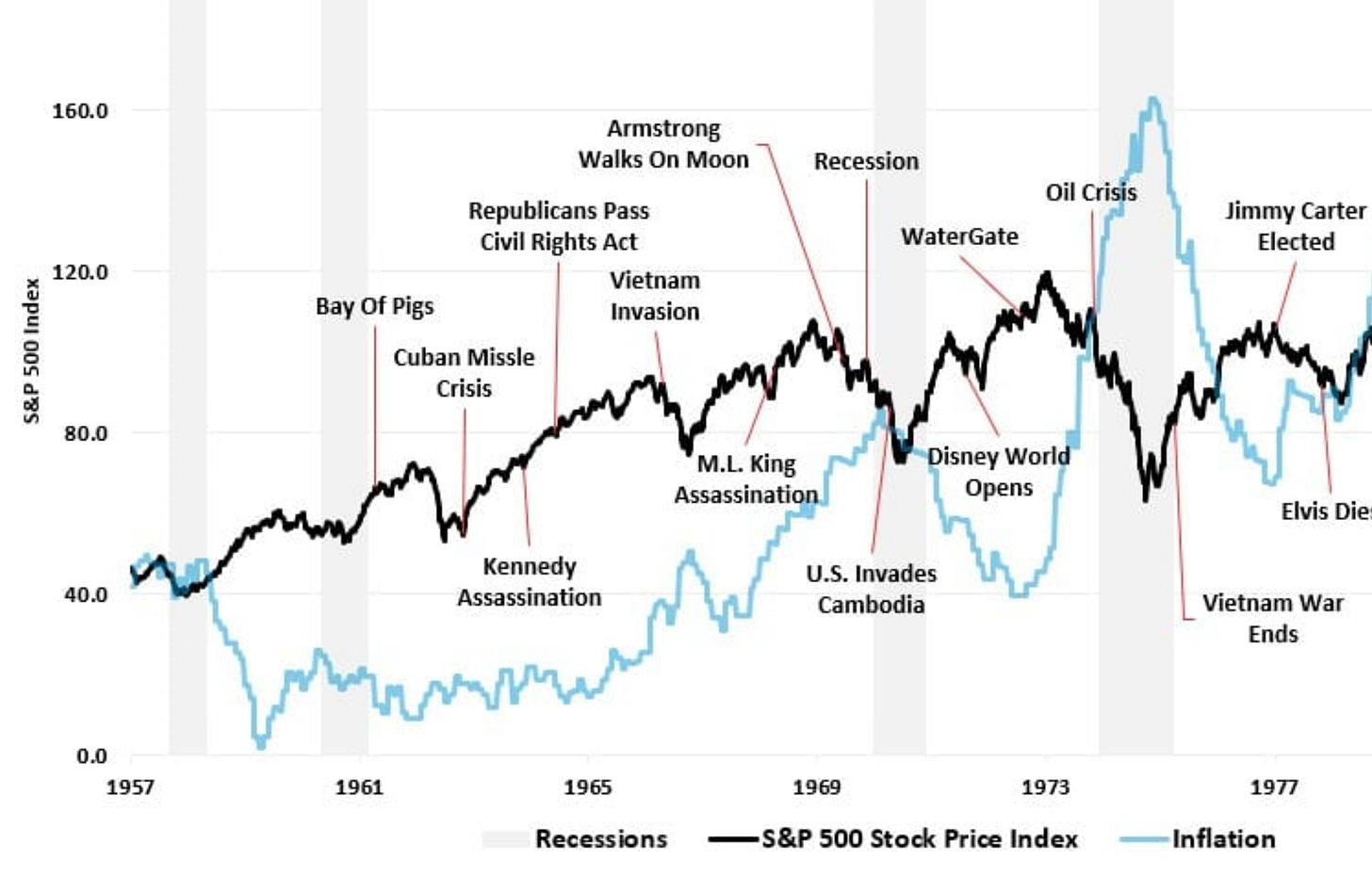

As I was working through big company assignments and so forth, the entrepreneurial part of me began to awaken somehow. I think it was a little bit because of the times. In the late 1960s, there was a roaring bubble stock market going on then and lots and lots of new companies and lots of press about new things, and real estate was really active. I was trying to decide. I figured out that I wanted to accumulate some capital. I just didn't want to have a salary and I was really fortunate. I met, socially, a fellow named Mort Collins, Data Science Ventures, and his partner who's my age, Jim Bergman. The three of us were good social friends. They had just launched their venture capital firm, Data Science Ventures, I think a $5 million fund, and they were pretty much at the center of the universe at that point because, in that era, no one really knew anything about computers. Computers were coming to Wall Street. All of Wall Street was befuddled about what to do with technology and computing and so forth. Mort had a PhD in computer science and he'd got himself positioned as a computer guru consulting to Wall Street. The financers of his venture firm were Warburg Pincus, Venrock, and New Court Securities—brand-name entities that were looking to him to be their specialist in all matters of computer and technology.

It was extremely unique at that time. On the West Coast people were focusing on technology, but not totally. Certainly on the East Coast and in the New York/Boston environment, it was totally unique. Mort Collins and Jim Bergman opened my eyes to the venture capital world, and the small company world and helped guide me, and at the same time, at Cresap I was working on a small company and I enjoyed it. I really enjoyed being able to get my arms around the whole thing and having a real impact on something. At the same time, I was reorganizing the Ford Motor Company, and the suppliers of the Ford Motor Company, and walking away from that thinking, “My God, this is the worst thing in the world to do, to work in one of these big companies.”

As I listened to them tell their stories about venture capital and what they were doing, it began to form in my mind that the skills that I had with consulting and the confidence I had with that, and then with my technical background, I probably could be pretty good at this venture capital thing if I tried it.

I got an opportunity to go up to Citicorp Venture Capital, which in those days was one of the centers of venture capital. There were a handful of big firms that were actively doing new things and Citi was one of them. They were very different than they are today. There were extremely well-run commercial banks that had strong entrepreneurial aspirations to do some other things and Citi was a fantastic organization. Citi had a venture group. Morgan Guaranty, now J.P. Morgan, had a venture group. First Chicago had a venture group. B of A had a venture group. Those were the four powerhouse institutions in the country. They all had a venture group, and they were largely wrapped around Small Business Investment Corporations. It became a very powerful earnings engine for them. So we did things like Cray Computer and Federal Express and lots of medical technology things, and oil and gas, natural resources, various things.

We also had a global business. At Citi, I was responsible for all the international work, in addition to doing domestic projects. So I saw venture investing in Europe very early starting in the 1970s, and that’s what helped me build the Accel portfolio over there. It was a pretty eclectic group of investors—, Arthur Patterson, my cofounder at Accel and at Adler— we worked together there. Pat Welch and Russ Carson. There were two or three other venture firms that came out of there.

3. “If you guys are so frickin’ smart, why are you here?”

We were making great money for Citi and we had our contemporaries who were making money for themselves, and so we were sitting side by side with them in the board meetings and we all had our opportunities to join this or join that. You’re at that age when you’re constantly evaluating everything and it started to open up. And there was a famous meeting we had. We always had these annual lunches with execs, and the Citi exec who was in charge of us at that point, we had this lunch and I’ll never forget it. It was winter of 1977 and we were all having these nearly fever-pitch conversations about breaking off together, different groups of us, or joining this or joining that, and we had this lunch and we asked him, “Okay, when are we going to get some equity here? What are you guys going to do for us?” and he leaned back in his chair with his big cigar and said, “If you guys are so frickin’ smart, why are you here?” And we all looked at each other. Next year, none of us were there.

Pat Welsh and I had talked a lot. I was going to join Pat and at the same time, I had gotten to know Fred Adler. I was very impressed. Fred’s a brilliant guy. So we started talking about— well, maybe we should form a partnership and raise some money and see where it goes. And so those discussions advanced and some other discussions advanced and I just woke one morning and said, “This is what I’m going to do.” So I left Citi, joined Fred, we formed a partnership, raised some money, started investing, went for a year or so, wanted to expand, felt good, went back to Citi, talked Arthur into joining us, and so the three of us built that and had an incredible run and made a lot of money.

I was pretty independent with Fred. But it still wasn’t my name on the door, and it wasn’t my firm, and he insisted on the lion’s share of the economics, which was fine. But at some point, it wasn’t fine, because I was producing as much or more than he was. There just came a time when Arthur and I looked at each other and said, “Well, it’s just time to do something else.” So Arthur and I departed. We had made enough money at that point. We had gotten liquid. So we had some walk-around change in our pocket at that point. I said I could go to the beach. It wouldn’t be a fancy beach, but it would be a beach.

I had enough money to do what I wanted to do at that stage of my life, pretty much. And so I step back and say, “What do you want to do?” I knew that I loved the venture business, knew that I was good at it, enjoyed working with Arthur, knew that we loved technology, and knew that we were pretty good. We had great experience both at Citi in an institutional framework, and with Fred. Fred was extremely entrepreneurial, a total hip-shooter, and so he taught us to be more fluid and a little more instinctive, a little more go-for-it. We taught him how to be a little more analytical, a little more disciplined, and so forth. It was a good balance. So I think out of those two formative experiences, institutional and highly entrepreneurial, we developed an investment style that has served us well. It’s a combination of being instinctive and being institutional.

4. “We didn’t want to put our names on the door.”

Arthur and I had a great relationship, and we knew we wanted to be in business together. So we formed Accel as a 50/50 partnership and started building Accel. We didn’t want to put our names on the door. We’d seen the perils of doing that. We wanted to get a name that was near the head of the alphabet because we had learned a lot of that with Adler and Company instead of Patterson and Swartz. We wanted a short name and so forth, so we found Accel, it’s an actual musical term. It’s short for “accelerando.” It means “picking up the pace.” It seemed to fit. We wanted to build a modern venture firm that would survive us and become an institution. That was the underlying objective. Actually, that was the sole objective.

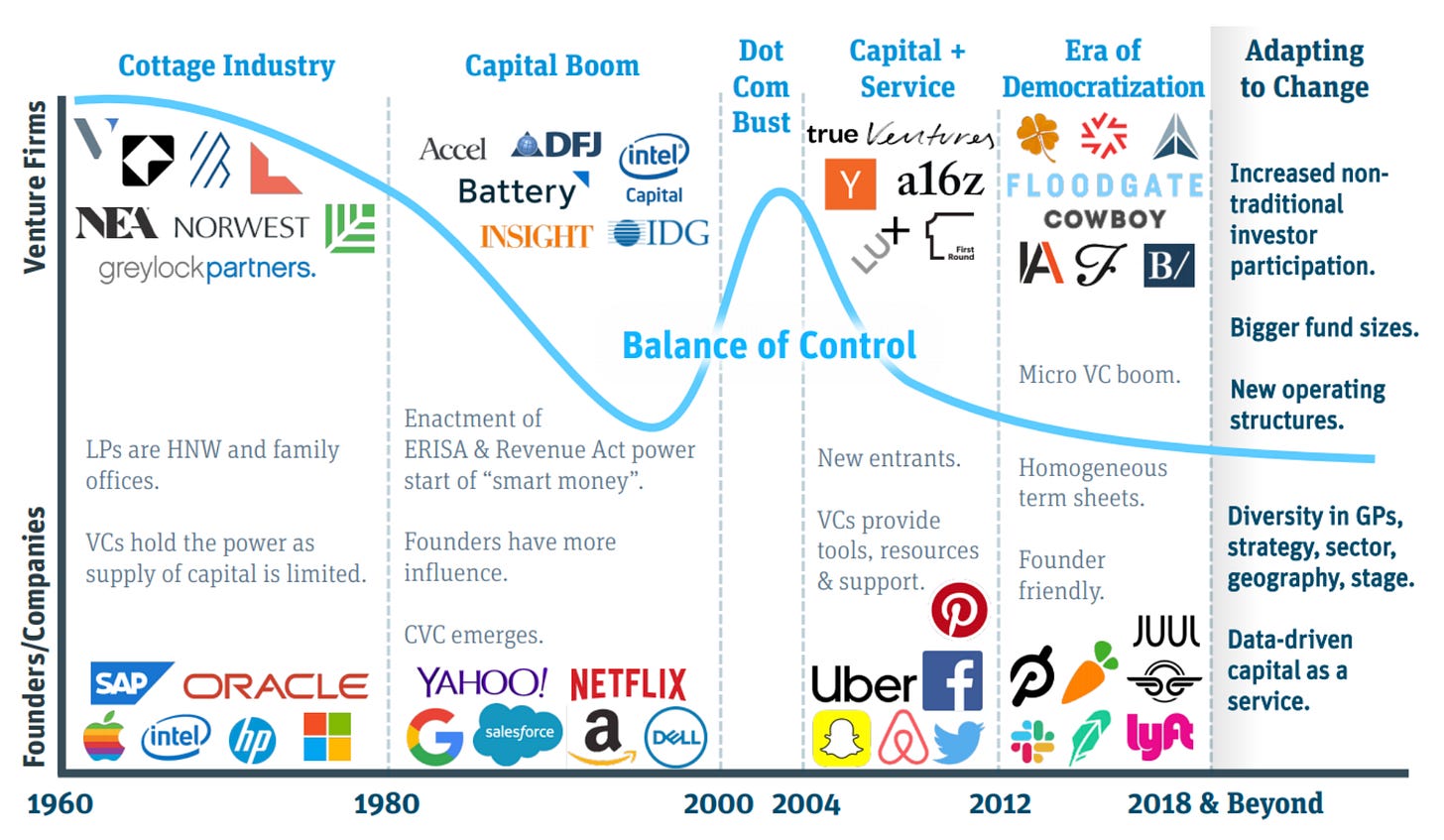

You had a lot of guys who were good generalists in the venture business who did a little bit of everything and just were basically backing good people, going with the flow, momentum investing, whatever you want to call it. Some weren’t terribly smart about what they were investing in. We felt that in the future you needed to really, really know the industry. You needed to know the industry almost as well as the entrepreneurs you were backing. That became a mantra— a guiding principle for us and that’s true to this day. Chance favors a prepared mind.

We worked really hard internally with all our young guys to get them to focus on certain investment themes and really get smart about it. We like to think that when we meet an entrepreneur and we start engaging with him, we know 90 percent of what he knows, and he knows the 10 percent that makes the difference and that we get excited about. And by knowing as much as we know, we can sort out the bad characters and bad opportunities. Most importantly, we can truly be helpful, because once you start doing that and then you build the ecosystem around those areas, you get the networks, you get the sources of information, the people, the executives, and so forth, it all starts to fit together and knit together. So that’s what we meant by a modern venture firm. We saw that we just had to be specialized and we had to be much smarter about what we were doing.

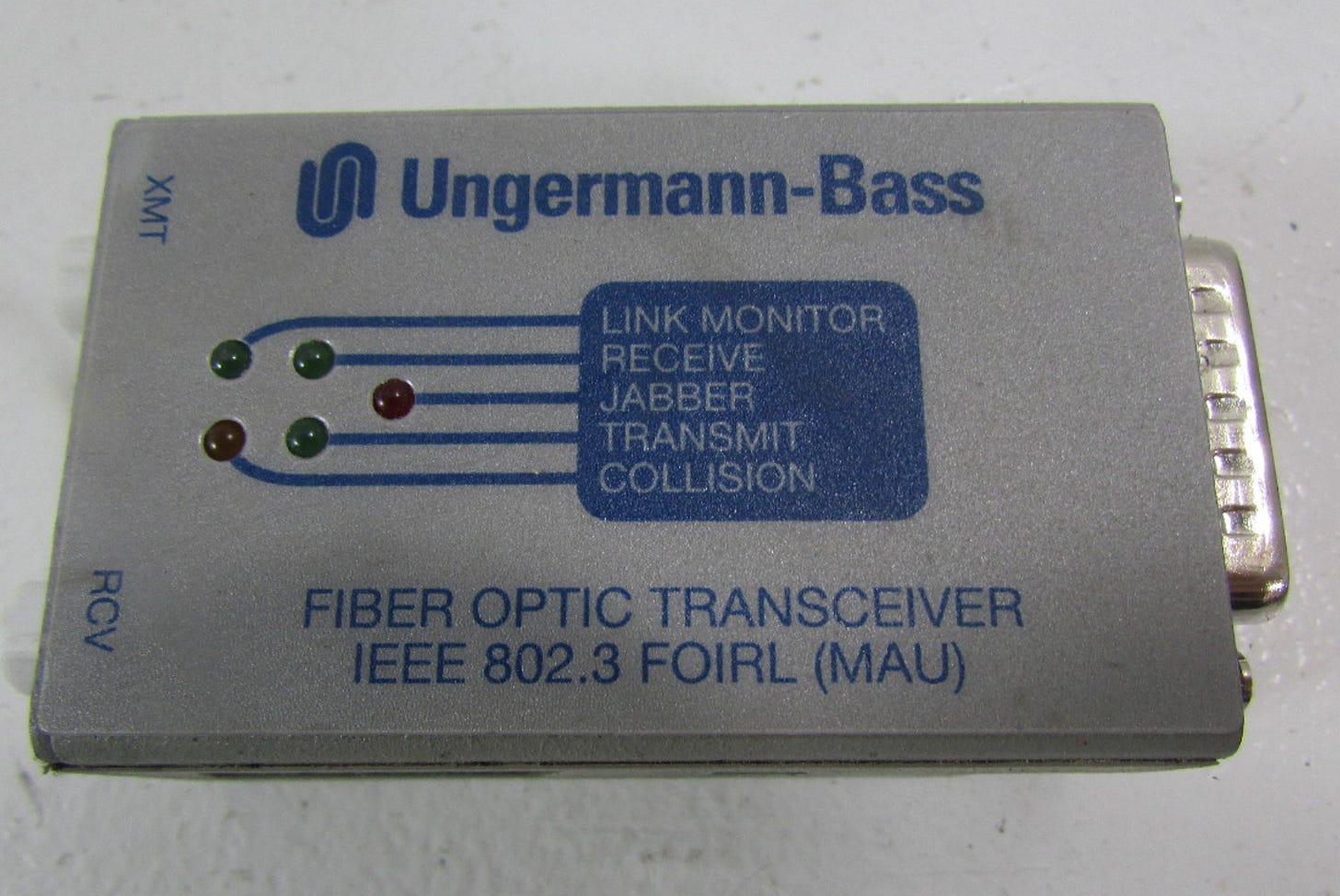

We decided to focus on communications, which in that case was extremely aggressive and unheard of, and software, which was modestly aggressive. By 1983, I fortunately had a sort of definitive experience with Ungermann-Bass and a couple of other communications companies, and so I very vividly saw what was coming. I mean, you can never predict exactly, but I knew it was going to be a great new area for investing for quite some time. Arthur had the same experience with software, and in 1983 most people would think investing in software wasn’t very smart. The common line was, “Well, the assets walk out the door every night.” So I think there were people doing it, but it wasn’t thought of as a major place to be investing. So both those areas were somewhat cutting-edge.

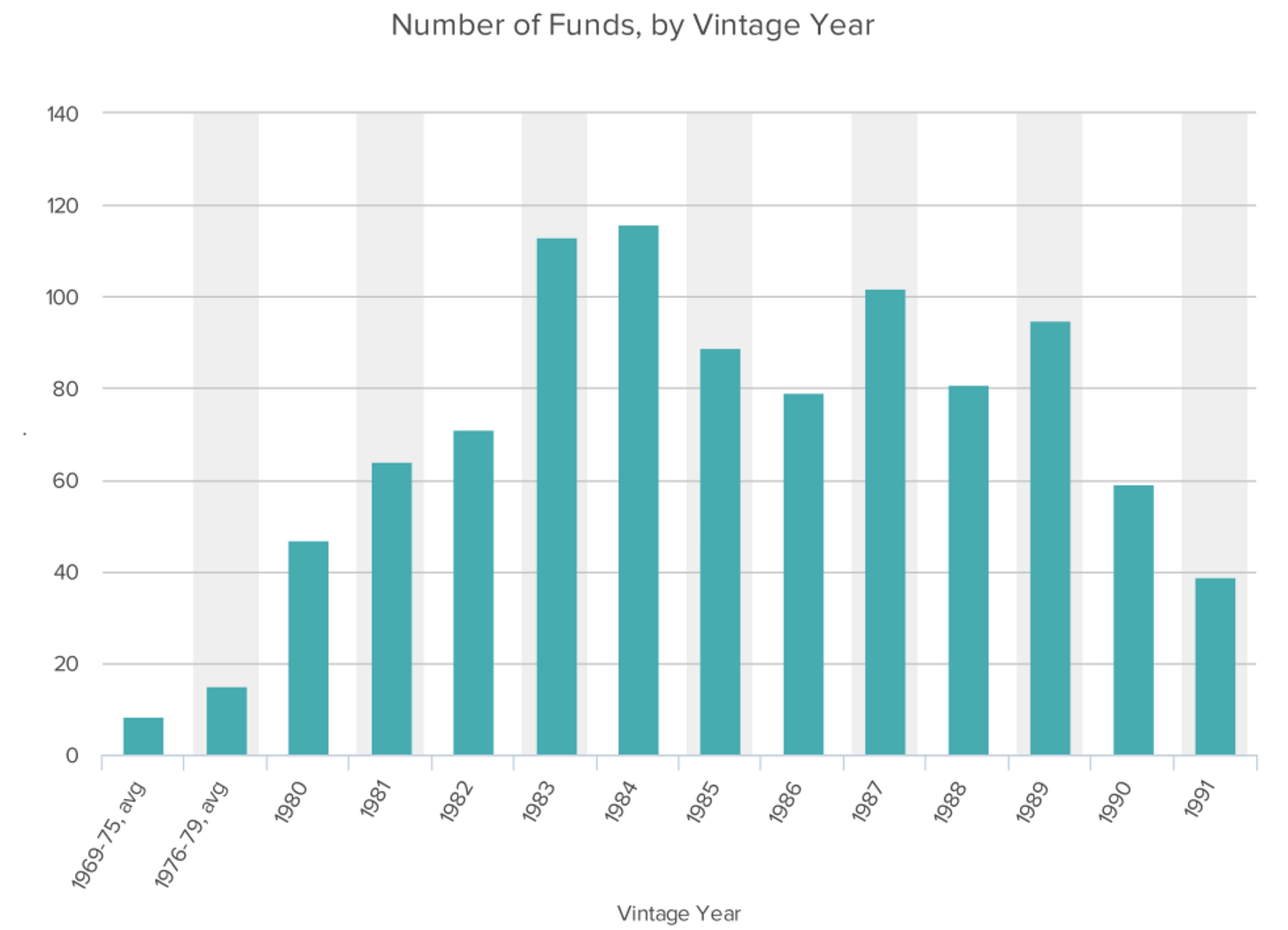

It was a lot of perspiration and running around, but in the total scheme of things it was pretty easy. We raised our first fund in the fall of 1983. It was sort of the tail-end of the bull market, and people were still pretty optimistic. Pessimism hadn’t set in yet. And we were coming off a number of successful IPOs, and we had a set of investors that followed us from Adler and Company to Accel. So we had a number of good early commitments, and we were able to pull it off. We closed it in December. But we decided to do something that pushed us. We knew that the business was going global and we had seen that. That’s where we differed significantly from the classic Silicon Valley guys, many of whom to this day still don’t quite get the globalization of venture, but in those days they clearly didn’t. Because of our Citi experience, and also our experience when we were with Fred, we already had a number of international investors. So we actually did two funds. We did a domestic fund and a parallel fund for foreign investors. We spent a lot of time in Europe and developed a number of good relationships that have served us well over the years.

5. “It’s just evolved from there.”

Putting a team together at Accel was stop-and-start; two forward, one back. The first younger person we hired was Paul Klingenstein and Paul was really strong. He wanted to do healthcare and biotech, and we had done some of that at Citi. Arthur and I both did a lot of devices and I did a fair amount of biotech with Fred. So we were very open to that. Paul was a really good, strong horse and so we could build a practice around that. Eventually, we decided to get out of that business, which was a strategic decision, and Paul went off and did his own firm and we’re good friends.

The next big step was the communications business. I really saw the opportunity to really double down on it, and so I started looking for a partner to bring in to enhance our practice there. I got to know Dixon Doll, and Dixon at that point was a pretty successful publicized consulting guy, consulting to IBM and others, doing a lot of press and conferences. I approached him and we formed a specialized communications fund, which enabled us to raise more money on the heels of the money we already raised. The really big thing was getting a marketing presence. You see people today doing “the big data fund” or “the iPhone fund.” This was I think the very first specialized technology fund that was really marketing-driven more than anything. It was a vehicle for me to get Dixon into the business and to raise more money, but most importantly it was a vehicle to attract marketing attention and really cement the Accel brand as the major telecommunications investor. That fund closed in 1986.

1987 was a pretty pivotal year. We’d raised some more money, we were starting to feel good about things, and we started going into recruiting mode. In that year we brought in two really important people: Jim Breyer, who joined us directly out of Harvard Business School, and Joe Schoendorf, who we had a relationship with. I was on the board at Ungermann-Bass. Joe was an executive at Ungermann-Bass. We got to know each other and then he went off to Apple and then he wanted to do something else. We brought him in as our connector in the Valley; he helped us with big corporate deals.

It’s just evolved from there. We’ve had our best luck with bringing in people in their thirties, either from a consulting background or from a product-marketing-technology background, and then training them in the venture business. It’s home-grown talent, largely. I mean you can supplement here and there around the edges, but the core group always ended up being the home-grown talent.

Accel has a flat organizational structure. The guys who are driving the firm are equal partners, there’s no hierarchy, and when we have partner discussions the associates who are not yet partners have as much to say as the most senior partner in the room. We try to have a very open, honest, nonpolitical, no-holds-barred discussion about the worthiness of the project. And that’s what I find works best.

We also try to keep sidebar conversations to a minimum, so if someone has an issue, we encourage them to bring it to the table and talk about it and let people hear. We work really, really hard at that. We once had an incident where Arthur had a startup project that was struggling. He had to sit there and listen to 45 minutes of criticism— good criticism, healthy criticism— about what to do or not do with the project. That’s what we want. Nobody has the right to just do what they want to do, and we try to get the young guys to get on that train as fast as they can.

6. “We approved nine companies yesterday. What were they again?”

I’d say that we probably weren’t as nimble as we should have been in the early days of the internet era because we were coming at it largely from the infrastructure side. We weren’t quite smart enough to get around on the application side of it. So we missed Amazon and missed Google. We didn’t have ourselves really organized well enough in that era to go capture those projects. I think we finally caught up later in the 1990s, and then on into 2000, we got ourselves reorganized and started focusing the right way.

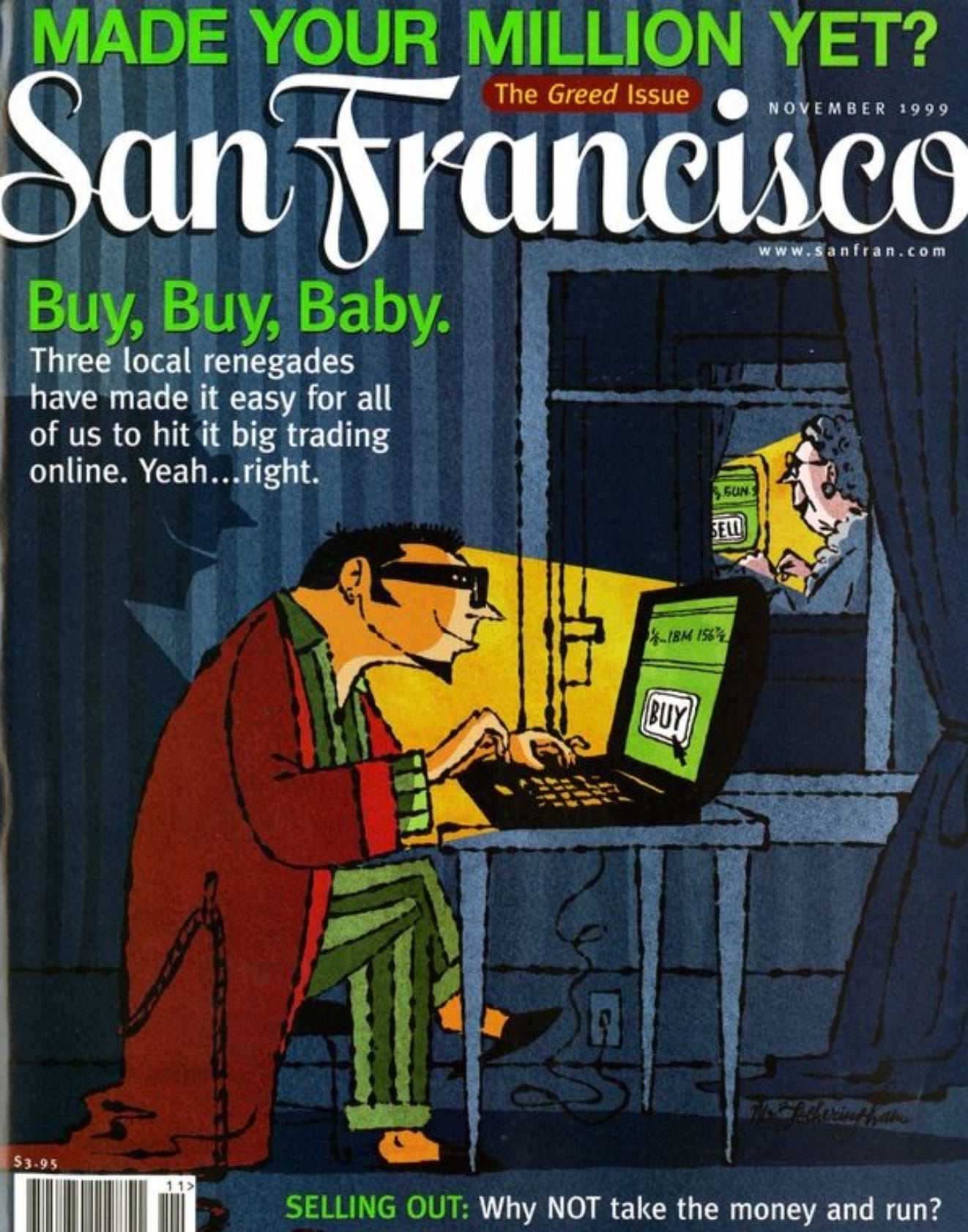

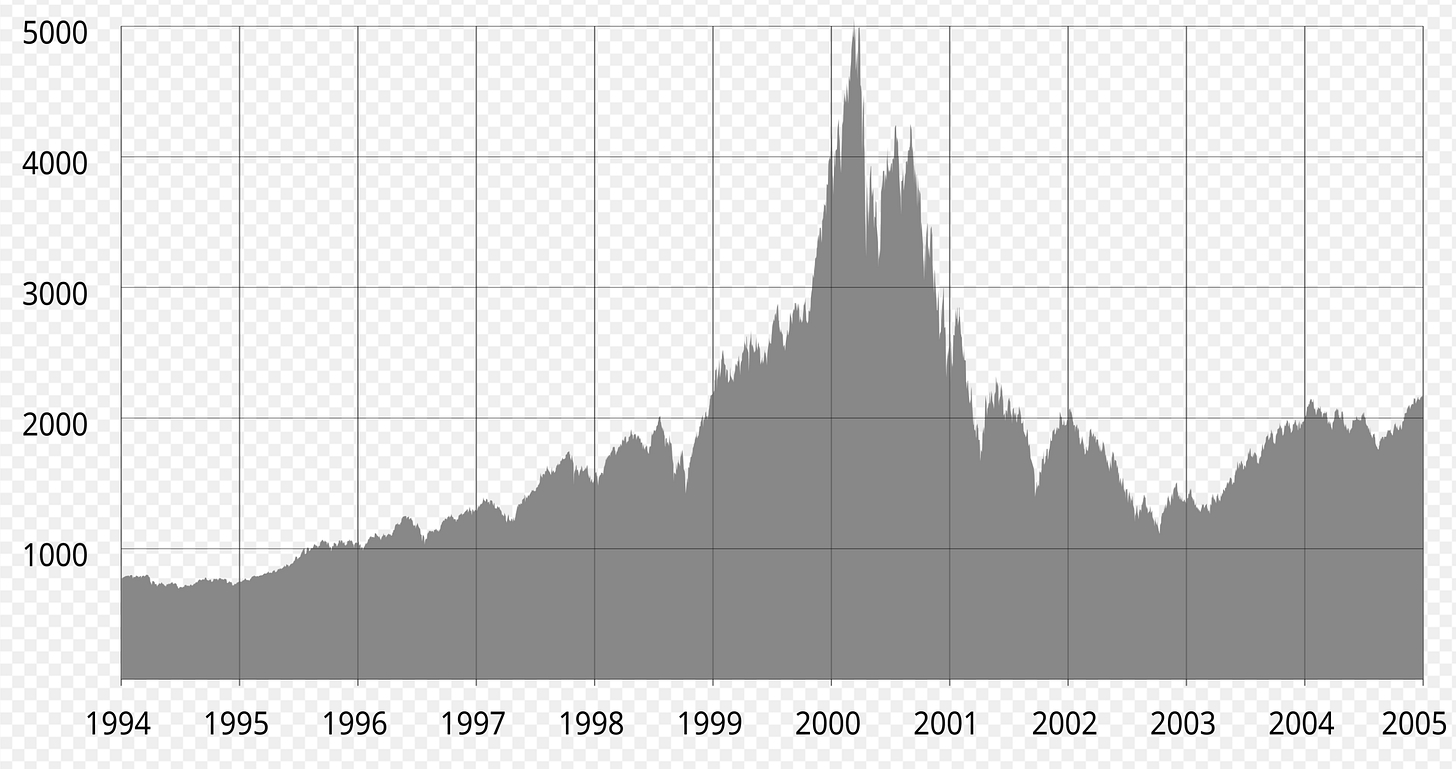

In 1997 it was very clear that a bubble was forming. I remember feeling in 1997, “My God, this is really good— from a stock market valuation point of view,” and then saying, “Sheesh, should we just get out here?” And then talking about it, thinking about it, and saying, “No. Let’s let it run a little longer,” and thank God we did because there was enormous value created from 1997 to 2000. Then we were into 1998 and 1999 and you knew this was craziness.

People around me were practicing a business I did not understand. We once got a phone call from a guy at a pay phone who had just arrived in Silicon Valley and wanted to come see us. He said, “I got three term sheets this morning, I’ve got to make a decision this afternoon. I want to come talk to you guys.” You’d go to a partner meeting where you literally had to fight your way through the conversation to get a project approved because there were so many projects on the agenda. I’d go home on a Monday night, wake up the next morning, and think, “Okay, we approved nine companies yesterday. What were they again?”

I write a family Christmas letter every year and for Christmas 1999 I wrote, “This is the best party there has ever been. It’s going to be a huge crash. We don’t know when to leave it.” You’ve been to parties where you get into it and you’re going and your head’s telling you that oh, boy, this is going to hurt, but you still keep going. That’s where you fall, and that’s what it was like.

7. “Let’s just liquidate…”

I’ll never forget when the curtain dropped in 2000. We were raising our new fund, Accel VIII, and we were sitting in the basement of the Four Seasons Hotel in the conference room there having meetings and the Blackberries and the signal wasn’t very good. The stock market was crashing. The market really took a big tumble in April that year. And by June we had several partners’ meetings and we said, “Look, it’s over.” What I’ve always said is, “You can’t pick the top and bottom. You can’t know in advance when it’s going to happen, but you can be pretty certain when it has happened, and then when it has happened you need to act.”

So we acted and we ended up shutting down eight or ten companies immediately. We’d walk into a board meeting and say, “Look, guys, we got X kajillion dollars in the bank here but this model is not going to work in the new world, and let’s just liquidate the company.” It became clear that this phase of the cycle was over and we had to respond to it and take some action.

Everybody was struggling. That was a difficult period for the firm because everybody was trying to figure out what it all meant. I decided this was a good time to start looking to do business overseas in Europe. I met with Kevin Comolli, we liked each other and formed a partnership. He and I worked hard together to get it off the ground and now Accel London is the single most successful venture firm over there. That was very satisfying, and it’s been a great exercise. So from 2000 to 2005 or so, I spent a large part of my intellectual effort doing that.

I think most of ’01, ’02, ’03 was pretty much heads down trying to salvage things and trying to work your way out of the mistakes you made. And so it was a very humbling time and there weren’t a lot of new investments made in that era. Arthur and I had seen these cycles and we knew we just had to stay alive and keep going, and eventually business would come back. We got ourselves reorganized around the application side as people started seeing opportunities in social networking and e-commerce and, lo and behold, along came Facebook

8. “Nobody knew how big it was going to be.”

Facebook was one that we were absolutely prepared for. We had looked at My Space, we had looked at all the others, and we had recruited some new people to help us in that area. So when we intercepted Facebook we were ready for it and it was a pretty easy decision. I mean nobody knew how big it was going to be. You could look at it and say, “Well, they’re going to get a hundred percent of the college market and the data so far is that college kids are spending three hours a day on the site.” So you do that math and say, “Well, we can monetize that and make a real business out of this.” Nobody knew whether you were going to be able to transition to the broader public or how big it ever would become, but we thought it was a good opportunity.

I think it was the individuals that we have, and the way we practice the business that created the opportunity. Did the Accel brand mean anything to Mark Zuckerberg? I doubt it. He probably was happy that it wasn’t some schlock firm, that we were good people, and that we had a history and so forth. But at the end of the day was that a deciding factor? No. I think we just handled it well. We had several good meetings with the team and everybody behaved themselves. I think it was just a number of individual actions that won the day.

9. “You’re trying to imagine the scenario.”

There are many different styles of investing, and the style that I’m most comfortable with is investing in people that I truly respect and who I believe have a unique ability to see through a problem in a way that others can’t. Then, the business has to be in an area that I understand and identify with and relate to. I’m less concerned about market size. Other investors may say, “Well, you’ve got to have a billion-dollar market.” My answer to that is, “That just has not been my experience.” Look at Ungermann-Bass. When I invested in that, the wildest expectation anybody could come up with is maybe it’ll be a $50 million business. Here we are, and local area networking is $50 billion or some double-digit billions. No one had any concept of how big the industry was going to be. A few would have turned that down because it was too small a market, too much of a niche market.

I’ll give you another example: wireless. We ended up getting killed because we were ahead of the standard and it was too expensive. We were a hundred percent confident that the product would work, but we couldn’t get ourselves convinced why anybody would want one. We spent six months trying to figure that out and we finally said, “Oh, well, yeah, we can see there’s a niche market here for accounting firms. Accounting firms want to do pop-up staffing in a company and they’re going to want wireless. You’re trying to imagine the scenario where wireless was going to be used and you think about that today and you say, “Well, what are you guys thinking? You can’t function without wireless.”

So, market size has never been a driver for me. I think it’s more about the people involved, and the inherent defensibility of what they’re doing, the technical edge, and then hope that the market’s bigger than you can envision.

10. “Watch for change.”

I think the venture industry, at its core, really hasn't changed much at all. There are aspects, sure, that have changed. But at its core of identifying an area, bonding with an entrepreneur, finding the right entrepreneur, finding the right sector, getting significant ownership, building the company, working as a director, and helping with the strategy; all of those basic building blocks are still very much part of the industry. I think there are large segments of the industry today that have gotten away from a lot of those fundamentals, but we keep coming back to it. We go through these periods and everybody thinks it looks simple, and then it all evaporates, and then people come back to the fundamentals again.

Obviously, a big difference now is the public perception of venture capital and just the sheer volume and pace of it. When we started, some projects were competitive, but largely you could spend three to six months analyzing something before you had to make a decision. And there was no public perception. You'd go to a cocktail party, and no one would understand what you did.

I think the one thing that has stuck with me is that the most effective leaders are the humble ones, the ones who are able to lead by example. They just don’t get caught up in it. I think we live in this celebrity world and I see many of the venture leaders trying to play the celebrity game and maybe it’s good for them, but I don’t buy it.

Alongside humility, persistence has always been a really necessary attribute. Persistence is really, really important in the venture business. It’s an industry where there’s very little feedback for long periods of time, so you have to have your own internal guidance system going and continue to be persistent.

Finally, I think it’s really important to have a vision about things. I’m constantly struck with how rare it is for individuals to truly have vision. I’m not talking about dramatic vision, but just a sense of where things are going. I think leaders really need to have that and exercise it in a way that’s not intrusive and not demanding, but just be guided by it continuously and not lose track of it. Change is everywhere, and it’s sometimes hard to recognize change. You need to learn to recognize it and then you need to learn to embrace it and run with it. That’s not always easy to do, but I think that’s the mark of a really good venture person. They’re really good at recognizing change and acting on it in some fashion. Watch for change.