When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will be complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance.

Chuck Prince, then CEO of Citigroup, July 2007

“Speak faster, do faster, decide faster.”

As she recounts in her memoir, Carrie Sun briefly worked as an executive assistant to Chase Coleman III, the legendary founder of Tiger Global Management. Established in 2001 as a public market hedge fund, Tiger Global would later venture into the private markets, adopting a combined strategy that would result in its flagship fund compounding at 21 percent on a net basis for two decades.

Renowned for shunning the limelight, Sun provides an absorbing portrait of Coleman1 at his zenith:

He did not give interviews. He did not sit for photos. Stories about him featured squiggly lines coalescing into caricatures of what appeared to be very different people. All this did not stop the financial press from crowning him Wall Street aristocracy or the society pages from speculating about his wife and kids and homes and money.

About the money: In the early part of the decade, [Coleman], debuted on a prominent list of the youngest billionaires in America. What was special about [Coleman], was his age, his net worth, and his industry. If [Coleman], continued compounding his wealth at, say, a rate of 20 percent per year—a conservative estimate given some of his reported returns; a number that does not even factor in carry, the profits he’d receive from owning and managing the funds—he’d have a net worth of over $5 trillion by the time he reached the age of Warren Buffett.

In his manner of operating, Carrie recounts being struck by Coleman’s preoccupation with speed:

I felt utterly at home working for [Coleman], whose cadence was not fast but faster. Not velocity but acceleration. Not process but process improvement. Speak faster, do faster, decide faster. During countless sits, after we had completed every item on the agenda, [Coleman] would ask me, “What else?” As in: What else can we do and decide on today? The rhythm of work was a constant drive to shorten the distance to decision. If you can decide on something now, do it. Don’t wait.

Moreover, Sun describes an organization, fashioned by its founder, wholly devoted to the pursuit of any information that could potentially confer an edge:

Everything was about the assist, the setup, the option, making the decision today that would illuminate paths for higher returns tomorrow—what [Coleman] called forward-looking decision-making, what I understood as extreme future orientation. The result, I became convinced, was that [Tiger Global] was able to paint one of the most complete pictures of what was happening in a given industry at any one point in time.

I began viewing [Tiger Global] as a decision factory, the main input of which was information—specifically, objective, and not subjective. [Coleman] did not care about hunches, gut feelings, or intuition; he concentrated explicitly on fact-based decision-making. Your output was as good as your input, which was why [Tiger Global] paid an army of people to amass information, and why it focused on getting on the inside, on gaining access to data of all types.

Which is to say, an organization wholly dedicated to the pursuit of what Sun came to consider lucre:

[Coleman] harbored no illusions about the game. This was, perhaps, his ultimate genius. I saw how the belief that the game was about more than just money was my fallacy, not his…I had fallen for them most readily because a large part of me was motivated to believe the lie, the myth—that a big, powerful crossover fund could care about something else, something greater, like morality or being a net positive to society; that the financial system could be fair and driven by something other than greed and self-interest. I used to think that [Coleman] was driven by a love of the game, whatever the game was, and that making money was a side effect. No. There was only money. Everything else was a side effect.

“They just kind of overextended themselves…”

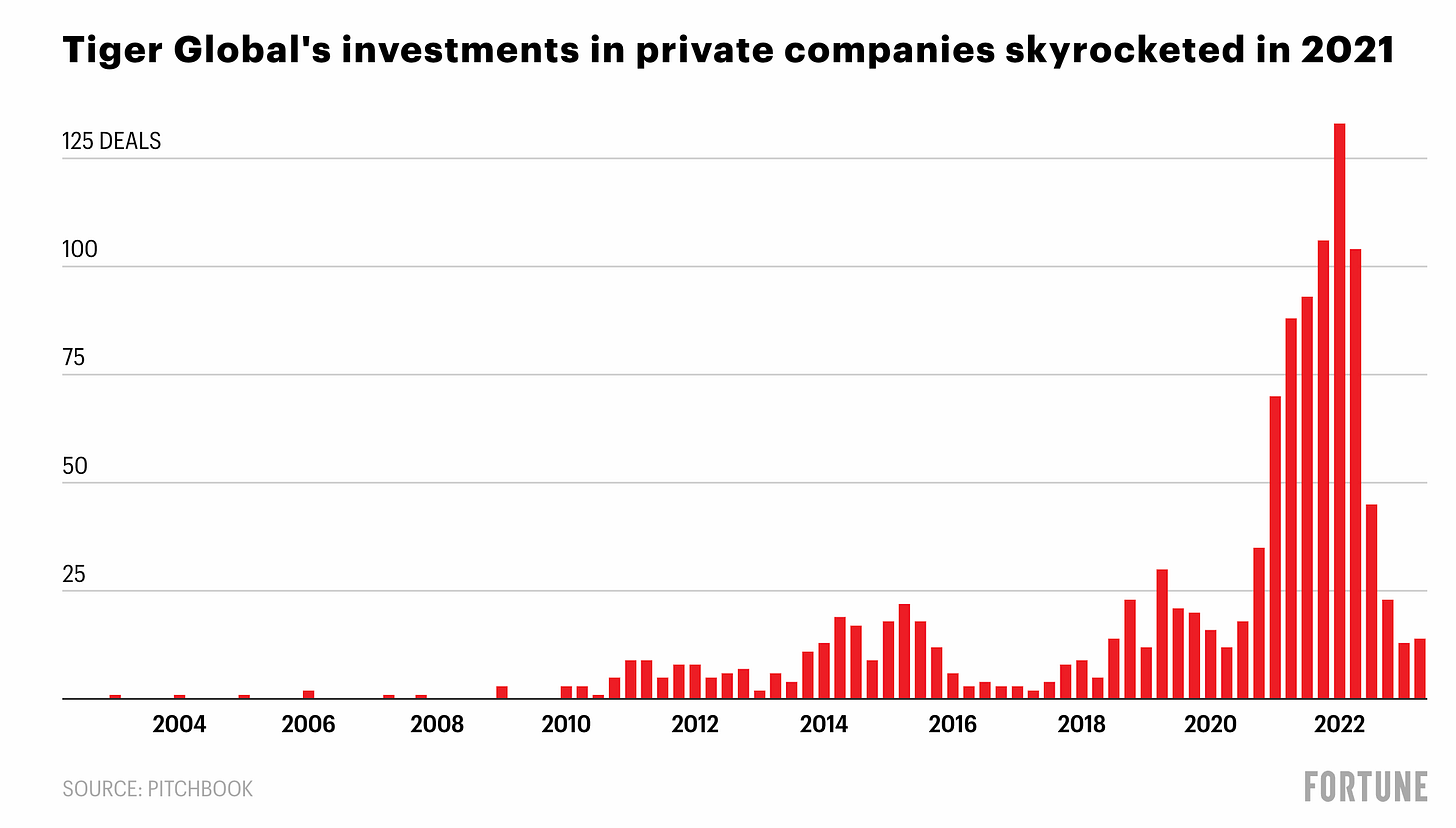

Inevitably, these incentives would gradually encroach upon, then overpower, decision-making at the firm. With the markets awash in intra-pandemic liquidity, Fortune reported that Tiger’s dealmaking went into overdrive:

By 2021—two years after private equity specialist Fixel had left the fund to start his own firm—Tiger had taken its need for speed up a notch. The pace at which the firm funded startups saw a massive increase, and Tiger garnered a reputation—met with much criticism from other venture competitors—for writing checks within mere days at lofty valuations…In 2021, Tiger backed the equivalent of nearly one startup every day—including weekends. “They kind of flipped a switch,” Kyle Stanford, a senior venture capital analyst at PitchBook, said of Tiger’s strategy in 2021. “They worked fast. They just kind of overcapitalized every company,” he says.

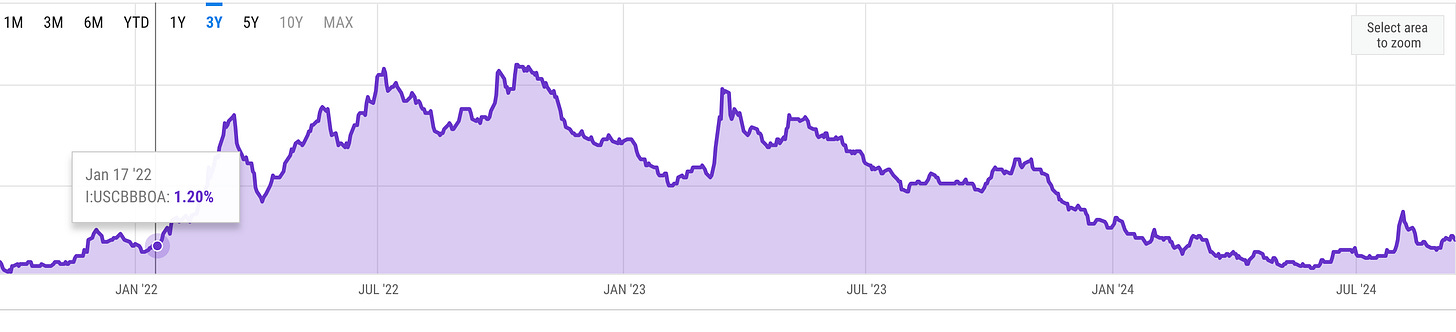

Unsurprisingly, when the Federal Reserve signaled its intention to aggressively raise interest rates in early 2022, liquidity dried up, the music stopped, and few were left dancing in either the public or private markets:

“Everything that they thought was going to happen, just kind of went away instantly, almost, in January” of this year, PitchBook analyst Stanford said. “To see them fall this fast is not surprising, they’ve obviously had trouble raising their next fund; they downsized it a couple times. And so 2021 just became this blip—that they saw something in the market and they were trying to capitalize [on] it. And they just kind of overextended themselves into VC.”

Tiger’s $12.7 billion private fund, launched in October 2021, reported 20% paper losses by the end of the following year. Tiger’s public portfolio was down 55% in 2022, though it would ride the market rally in 2023. Tiger’s latest venture capital fund closed in April of this year having raised only a third of its intended $6 billion target.

Use it and Lose it

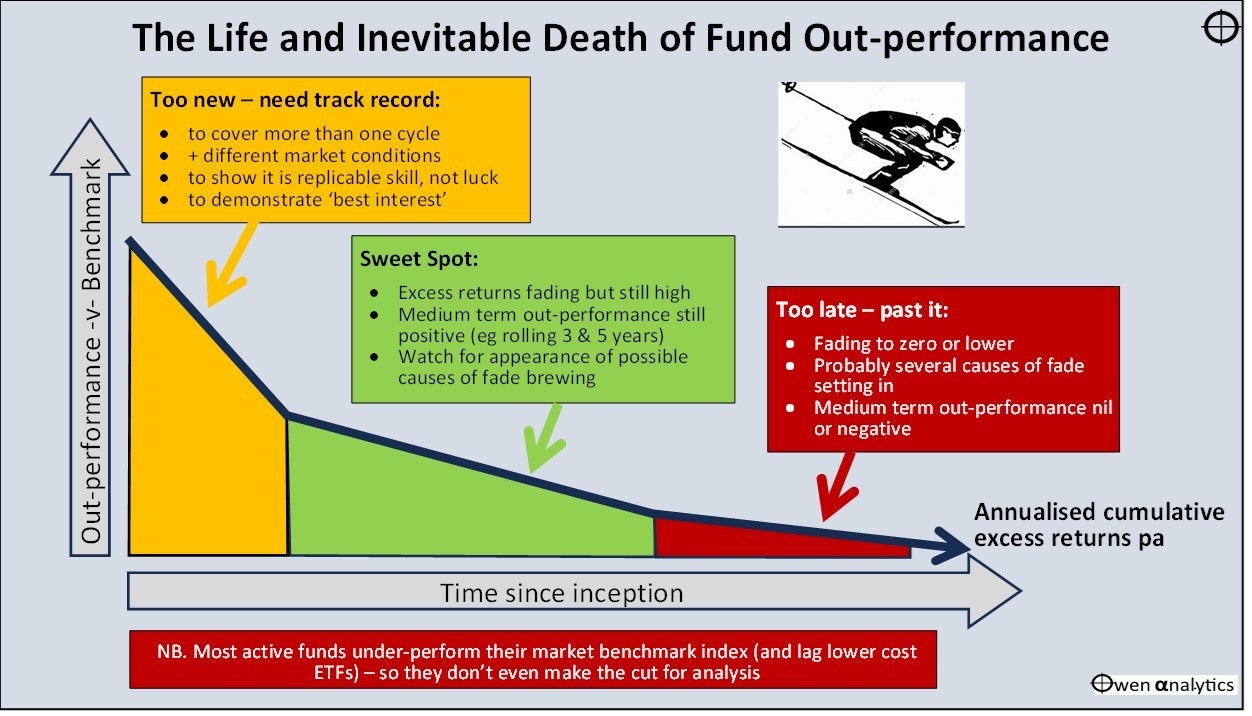

I was reminded of Tiger’s travails when reading Ashley Owen’s bracing piece on performance decline amongst fund managers:

All active fund managers peak early in their careers (in terms of beating their market index anyway) - and then it is all downhill from there. Even for the best in the world.

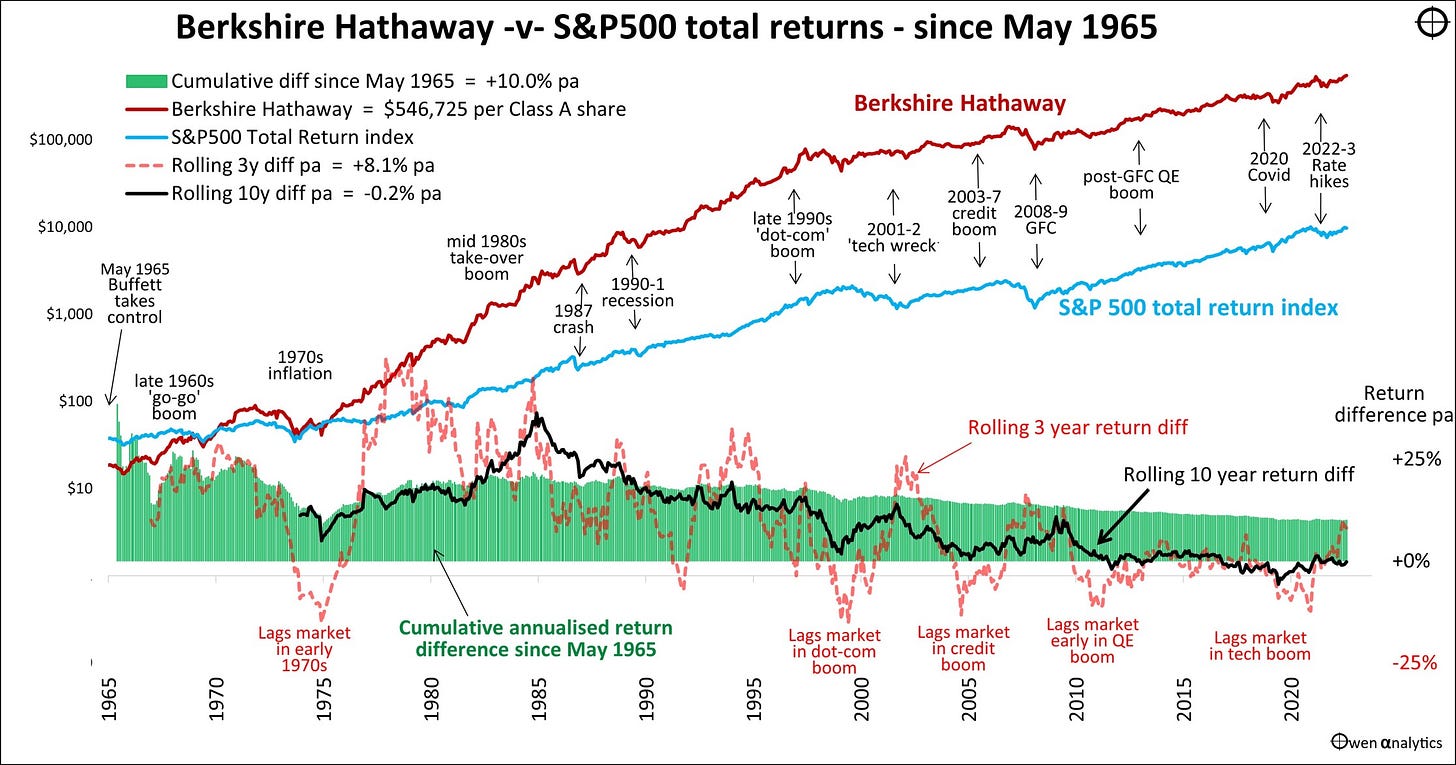

Owen argues this reversion to the mean is inevitable, with even Buffett’s performance being found to fall short in the latter stages of his career:

Alongside the law of large numbers, Owen identifies 14 other reasons that may account for this widespread decline in performance, which I’ve subsumed under four broad categories:

Market:

Inability to adapt to new market conditions

Arbitrage of edge2

Changes in market conditions affecting strategy effectiveness

Risk, Strategy, Luck:

Excessive speculation during booms leads to significant losses

Difficulties in scaling strategies due to increased AUM3

Initial success due to luck (survivorship bias)

Psychological, Personal:

Loss of drive and focus after achieving success

Aging, fatigue, or boredom

Distractions from wealth and outside interests

Family problems

Lack of self-reflection

Organizational, Structural:

Reduced financial incentives due to selling out or down

Distractions from managing multiple funds, strategies, and complexities

Decreased agility due to increased size and management layers

Increased conservatism due to increased responsibility

Thinking back to the manner of operating and incentives at play at Tiger Global, it isn’t difficult to see why matters went awry when the tides of liquidity went out.

"Invert, always invert."

Believing his list to be comprehensive, Owen uses these factors as a filter when meeting a fund manager for the first time:

I have spent countless thousands of hours over the past 20 years meeting fund managers. In almost every case I am impressed by their reasons and strategies for their stock holdings. They always have very convincing stories about their stocks. But I am looking at something else.

While we are talking, what I am really thinking (and sometimes tell them) is:‘I love the stock stories but that is not the main issue. The issues is - I KNOW your performance is going to fade. I can see how much it has faded already, and I know that it will probably continue to fade in the future. What I’m really trying to do is identify what are the causes of performance fade in your particular case, and whether they are likely to accelerate the decline’.

Of course, such an approach accords perfectly with Charlie Munger’s now-famed exhortation to invert. From his 1986 Harvard School Commencement Speech in Poor Charlie’s Almanack:

What Carson did was to approach the study of how to create X by turning the question backward-that is, by studying how to create non-X. The great algebraist Jacobi had exactly the same approach as Carson and was known for his constant repetition of one phrase: "Invert, always invert." It is in the nature of things, as Jacobi knew, that many hard problems are best solved only when they are addressed backward.

Given the context of this post, Munger’s concluding remarks appear perfectly apt, both for students and aspiring fund managers:

Einstein said that his successful theories came from "curiosity, concentration, perseverance, and self-criticism." And by self-criticism, he meant the testing and destruction of his own well-loved ideas.

Finally, minimizing objectivity will help you lessen the compromises and burden of owning worldly goods, because objectivity does not work only for great physicists and biologists. It also adds power to the work of a plumbing contractor in Bemidji. Therefore, if you interpret being true to yourself as requiring that you retain every notion of your youth, you will be safely underway, not only toward maximizing ignorance but also toward whatever misery can be obtained through unpleasant experiences in business.

It is fitting that a backward sort of speech end with a backward sort of toast, inspired by Elihu Root's repeated accounts of how the dog went to Dover, "leg over leg." To the class of 1986: Gentlemen, may each of you rise by spending each day of a long life aiming low.

Though Sun uses pseudonyms in her memoir, the identities of those involved are well known. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carrie_Sun

“Martha becomes rich over several years by employing her intuition with respect to this pattern. Eventually other investors will catch on. They will either recognize the pattern the same way Martha did or they will try to understand how Martha is making so much money and will emulate her. Eventually, Martha's intuition will become obsolete. Previously, not many people took notice of management transitions and Martha would acquire stock at almost the same price as where it was trading prior to the management change announcement. Now, stocks that Martha wants to buy spike up immediately after the management change announcement. They go up so much that the risk / reward of the investment is no longer practical. As a result, Martha has a much tougher time making money even though she has much more investing experience now than she did several years ago.” Ravee Mehta. The Emotionally Intelligent Investor

Owen: “…this is Buffett’s main problem”