A talent is formed in stillness, a character in the world's torrent.

― Goethe, Torquato Tasso

Pas"sion (?), n. [F., fr. L. passio, fr. pati, passus, to suffer.] 1. A suffering or enduring of imposed or inflicted pain; any suffering or distress. 2. The state of the mind when it is powerfully acted upon and influenced by something external to itself; an inordinate desire; also, the capacity or susceptibility of being so affected. 3. Capacity of being affected by external agents; susceptibility of impressions from external agents.

Preface

This is the first in a series of posts attempting to explicate, in his own words, Chamath Palihapitiya’s approach to markets and decision-making. Given the singular circumstances of his childhood, Part I focuses more on the particulars of his upbringing and early career.

Disclaimer

The following post is fashioned from Chamath Palihapitiya's public statements, interviews, annual letters, and blog posts. Sources are cited. Despite every attempt having been made to preserve their original intent, errors and misinterpretations are, of course, possible. Caveat lector.

Contents

Timeline

Immigrant Grind

Boundary Conditions

Urgency

Optimizing for Ownership

Network Effects

Brittle Success

Move Fast and Break Things

Thinking in Bets

Sources

Footnotes

Timeline

Born: 1976

Emigration: c.1982

University of Waterloo: 1994–1999

BMO Nesbitt Burns: 1999–2000

Winamp & Spinner.com: 2000–2001

AOL: 2001–2005

Mayfield Fund: 2006–2007

Facebook: 2007–2011

Social Capital: 2011-Present

Immigrant Grind

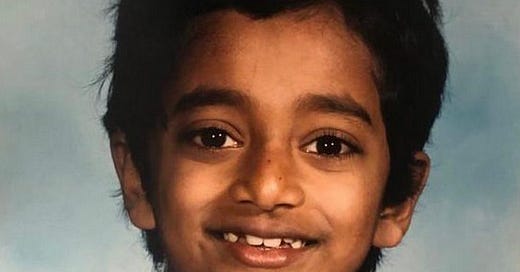

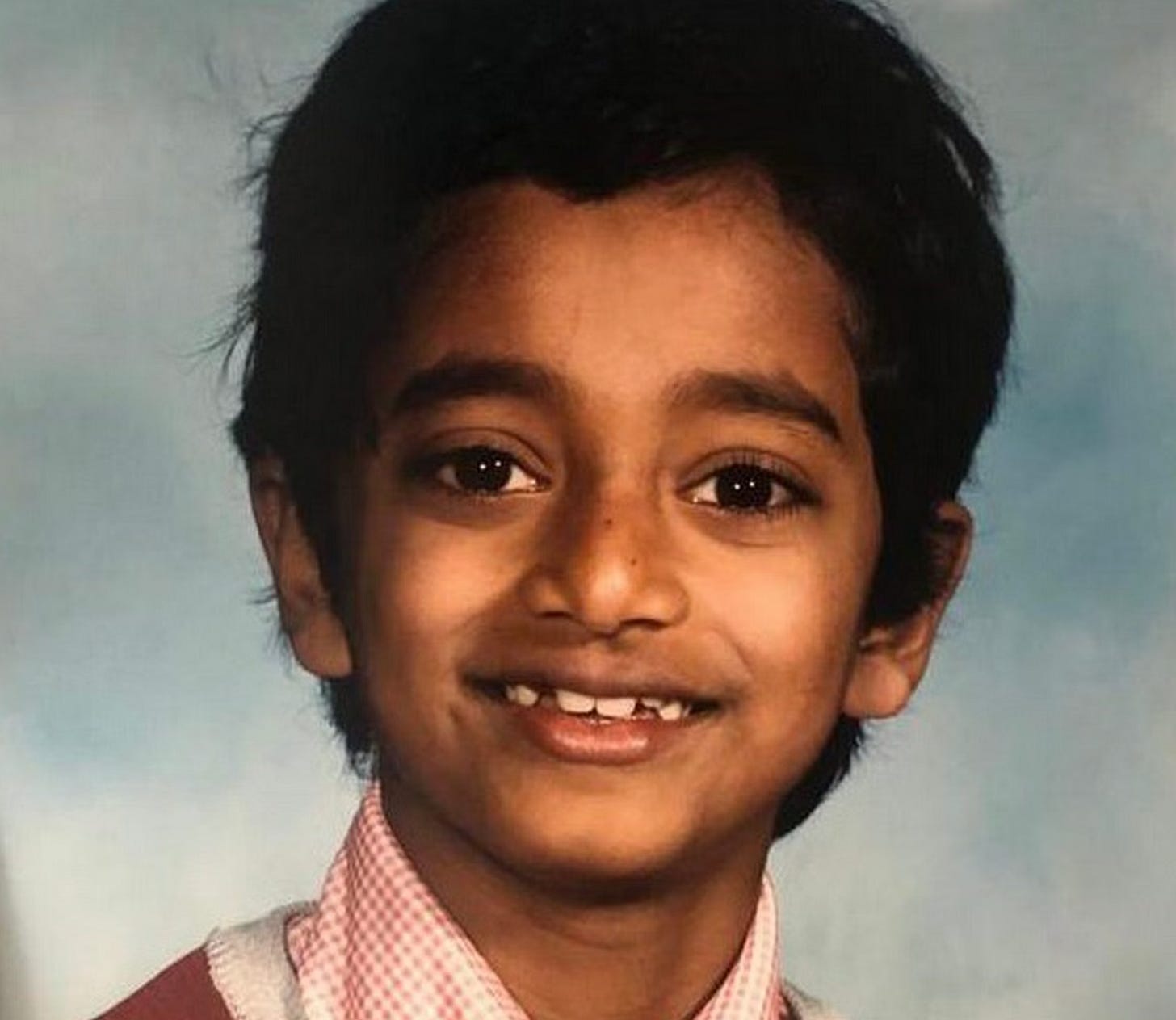

I was born in Sri Lanka in 1976. My mother was a nurse, and my father worked in the health ministry. When I was around six years old, my dad got a post at the Sri Lankan High Commission in Canada, so we emigrated. We were only supposed to stay for four years, but because of the onset of the civil war in Sri Lanka, my dad did whatever he could to stay in Canada.1 He filed for refugee status when I was 11, lost his government job as a result, and thereafter was effectively ostracized. We essentially gave up everything, and lived in a 400-square-foot two-bedroom apartment above a laundromat. My dad struggled to find steady work after losing his government post, and there was a lot of drinking. My mom worked as a housekeeper, and then became a nurse aide. They had to grind every month to make ends meet. [1]

I remember helping my parents fill out their tax forms. Supporting a family of five, the most they ever made in a year was 32,000 Canadian Dollars.2 We had such a strict budget that we didn't even have a car. My mom and I were responsible for the shopping, so I learned very early on how to look for coupons, and how to buy things that were on sale. We had a very basic diet because you have to budget really precisely when you’re living on so little. Really, it's incredible the sacrifices my parents made: they bought our school supplies, provided us with music lessons, and ensured we had jobs. We lived the typical immigrant grind, but we benefited from free school and healthcare. Once, my dad even pulled me out of a bad school and convinced the principal at a better school to admit me. [2]

On the flip side, my father drank too much at times, which I bore the brunt of. He was angry and he used me as a mechanism to alleviate his frustration. There was a tree outside the apartment where we lived, and my father would sometimes send me out to select the tree branch that he was going to hit me with. Can you imagine, if you're an 11-year-old kid, what it’s like having to deal with that? What do you do? Well, a child quickly learns how to estimate his father’s anger, as well as the strength of the tree branches. Other times, he used a belt. There was a certain belt that he wore that had a protruding buckle, and if you were going to get hit, you just wanted to make sure that the buckle wasn’t facing out because that really hurt. [3]

Honestly, it felt like growing up in a war zone. I learned I had to evade my father to survive, and I learned that I had to lie to avoid a lot of pain. I was hyper-vigilant as a kid, and as I grew older, I became hyper-aware, hyper-detail oriented, hyper-everything. It was all rooted in a profound fear because I just didn't want to be at the receiving end of that kind of physical and emotional damage. [4]

Growing up in a household like that, it's actually easier to point to those few moments where I was happy, or I felt compassion, or I felt safe. Those moments are seared in my memory in a way that I just can't describe. For example, when I was in grade five or six, I volunteered with a few other kids to help in the kindergarten of my school. At the end of that year, as a small gesture of thanks, the teacher took me and the other volunteers to Dairy Queen for a meal. Now, because we didn’t have the money at home, I had literally never gone to a restaurant before. I will never forget the first time I tasted that hamburger and fries at Dairy Queen. Most people would take a meal like that for granted, but I just felt so special to be given it. [3]

Another example, we had a really strict shopping budget, but at the end of the year, my parents would buy a cheesecake that had been discounted from $7.99 to $4.99. My parents would buy that once a year, and we probably did that six or seven times. You can’t imagine how special my two sisters and I felt as we cut this cheesecake into five pieces, and watched the New Year's Eve celebration on TV. It felt like everything.

That's how life was; for better or for worse, that's how I remember it. [3]

Boundary Conditions

I had no friends in high school. Being so ashamed of the world that I had to live in, I just didn't want to bring anyone into it. This meant I didn't have a cohort to shape my expectations around the future: about going to university, getting a public sector job, buying a house, etc. In fact, because I was so afraid to venture out of my own house, I never really saw what middle-class life was like, and so I never aspired to it. [3]

I wasn't popular or invited to parties. I spent my nights at home, reading Forbes and Fortune Magazine, dreaming about being successful like Warren Buffett and Bill Gates. I grew up in Ontario right at the point when the telecom boom was underway. Companies like Nortel, Mitel, and Newbridge Networks were all built in the suburbs of Ottawa by larger than life entrepreneurs, such as Terry Matthews and Michael Cowpland. They made their fortunes in the process, and I wanted to be like them. I knew that my family’s station in life was not the destination, and I had to get out. It's not like I had parents who would question my decisions; this was all foreign to them. Being the child of very accomplished parents is a huge weight, but I didn't have that. My desires were ultimately framed by these rich people who I had never met, and they’ve been wired into me ever since. [2]

When you’re born natively into a country, it’s straightforward to fit into all the pre-existing societal norms. If you’re an immigrant, you’re more prone to feeling like an outsider and questioning things. These can be good boundary conditions for wanting to achieve something.3 I was fortunate because my expectations weren’t shaped by the people around me, and so I was free to create my own expectations. For a long time, I used to think to myself, “Woe is me, look how hard my life was.” In hindsight, I was blessed to have the difficulty: the bar was so low, I couldn’t do anything but go up. [5]

Urgency

I worked a lot as a teenager. Even when I was in school, I was going back and forth. I never really went out; I never took any vacations. Honestly, I wasn’t a well-rounded person: I was just running on a treadmill, obsessed with trying to get ahead. I didn’t necessarily know where I was going, but I had this urgency inside me to succeed. [1]

My first job was at Burger King when I was 14 years old. I would do the closing shift from 6 PM until about 2 AM. The Burger King was located in Ottawa, close to the Ontario—Quebec border. Now, in Ontario, the drinking age is 19, but the drinking age in Quebec is 18. You can see where I’m going with this. To kids in Ontario, that one year made all the difference. They would come to the Burger King after getting completely drunk, and they would light that place on fire: vomiting and urinating everywhere. You can’t imagine how mortifying it was for me to be there in my uniform, watching this unfold. Worse, come closing time at 1 AM, I had to clean it all up. Night after night. It was a grind, but it taught me a valuable lesson: I really did not want to be doing this kind of work. [3]

I got another job during a summer in high school, where I worked at an I.T. help desk. The manager told me that if I could clear all six thousand trouble tickets before school restarted, he would take me to McDonald’s. I cleared the tickets, we went to McDonald’s, and I ate six Big Macs. He was flabbergasted. Quite honestly, even I don’t know how I was able to eat six, but I probably had some training from when I worked at Burger King. [1]

Optimizing for Ownership

I worked as a Derivatives trader for a short while after graduating from college. I actually suffered a lot of losses on the job, but I was fortunate to be introduced right away to this idea of managing risk. I also had this incredibly lucky thing happen to me while I was there. My nickname on the trading desk was “Sherman”, nobody wanted to say Chamath so they called me “Sherman” instead. My boss at the time, his name was Mike Fisher, had recently made a lot of money, and one day he said to me, “Sherman, how much debt do you have?” I said, “I have like $27,000 of debt.” He wrote me a check and said, “You go pay that debt off right now.” I walked downstairs, paid it off, and came back upstairs. He told me, “That’s the value of equity.” [5]

Well until my early thirties, a third to a half of my paycheck would always go back to my family. I felt like I was constantly having to run uphill, and I could never really live my station in life. When I made $50,000 a year, it was like making $25,000; making $100,000 was like making $50,000; $200,000 was like $100,000. My boss’s kindness not only lifted a burden from me, it taught me an incredibly valuable lesson. I had been trading stocks on the side for a while, but I hadn’t realized that I was actually buying pieces of companies, and that this equity could create real wealth.4 [5]

After leaving trading, I got a job offer to go work with a small startup company in California called Winamp, which had just been bought by AOL. The salary was a lot less than I had been making as a trader, but Winamp also offered me about 5,000 shares as part of my compensation package. When considering the offer, I built a spreadsheet and calculated how much money the shares would have been worth had I joined in a different year. It turned out there were a couple of scenarios where they would have been valued between $3 million — $4 million, and that also made a big impression on me. [5]

I joined Winamp, took the 5,000 shares, and the stock price went in half. I made nothing from it, but the lesson was invaluable. When I went to Facebook later on, I was in the senior management team, and I remember Mark Zuckerberg and I were negotiating my compensation package. I told him that I was optimizing for ownership and I wanted him to give me all the ways that I could make money via equity in the company. One way he came up with was that I would receive 25 basis points of equity for hiring three director-level employees. Later on, I decided that I didn’t want to hire directors, and I’d rather recruit from within and promote up. I went back to Mark and I said, “Let’s just tie it to users.” Those weren’t billion-dollar decisions at the time, but they turned out to be, and they’re all tied to that one moment where my boss Mike Fisher said, “Sherman, go pay off your debt.” [5]

Network Effects

When I was 26 years old, I was a corporate VP at AOL, running the AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) and ICQ businesses. I was actually pretty good at managing because early on I learned how to get to know people and how to understand their motivations. Part of it was also just the general curiosity that I had about people. I didn’t have many friends growing up, and suddenly, I had the opportunity to meet interesting people, and ask them about their stories. It was easy to disarm people by simply asking, “Tell me about yourself.” [1]

AOL had acquired both Spinner and Winamp, and we operated in a building in San Francisco that housed a bunch of other music startups, including Napster. That's how I became pretty good friends with Sean Parker. Several years later, Sean and I did a deal when he was working at Plaxo, and then he joined Facebook. I had moved to the East Coast in the intervening period after becoming a mid-level director in the music businesses of AOL. One day, he called me out of the blue and said, "Hey, where are you?" I told him I was in DC, and he said, "Perfect, I just joined this company called TheFacebook.com. I'm here to see my parents, and I brought my boss. You want to meet him?" [4]

So, in 2005, Parker showed up at my office in Dulles, Virginia, with Zuckerberg, who must have been around 19 at the time. Zuckerberg was like a caricature out of the movies, wearing a North Face hoodie, shorts, and flip-flops in the middle of November. I thought, “This guy must be a genius because it's really cold outside. He must know something the rest of us don’t.” [4]

I talked to him, didn't think much of it, but went back to the team and said, "This company is really growing, and it's the next network effect that comes after our network effect in AIM and ICQ." They basically said, "Listen, kid, we are in the middle of deconstructing this hundred billion dollar merger with Time Warner. We're not buying anything, but we'll give you the green light to do a business deal with Facebook." [4]

So, I went to Parker and Zuckerberg and proposed integrating AIM into Facebook. Remember, this was 2005 and 2006, so they didn't have Facebook Messenger or WhatsApp or anything like that. If you used the product at the time, you'd see this little running man logo or ICQ logo beside your name, click on it, and our app would pop up for you to communicate with people. At the time, that was relatively novel, but it was pretty clunky. Very quickly, the Facebook board said, "This is horrible, get out of this deal." So, Parker called me with two pieces of news: first, he was leaving the company, and second, I needed to unwind this deal. That's how I got to know Zuckerberg at the time. We unwound the deal, but within a year, I was working at Facebook. [4]

Brittle Success

Before joining Facebook, I was approached to become a principal at Mayfield Fund, which, alongside Sequoia, is one of the original Venture Capital organizations in California. I took the job partly because I wanted to move back to the West Coast, but primarily because I wanted to be an investor. I had actually never aspired to be an executive or an entrepreneur, but the idea of allocating capital had appealed to me for a long time. [4]

I took the job, but soon realized Mayfield was an organization that was on the tail end of its best years. They were not only coming to terms with the mortality of their partners, but also just how brittle success in Silicon Valley can be, if you miss out on a new wave of innovation. I learned a lot, but I was only there for six months, and then I went to Facebook. [4]

As an aside, I actually interviewed at Sequoia once, but Mike Moritz talked me out of it. He psyched me out. We spoke for an hour and a half, and at the end he said, “You should not do this job. It's really, really hard.”5 At the time, I didn’t really believe in myself, and I thought, “He’s right. I can't do this.” I had a lot of fear internally, and so I just went back to my old job. Looking back, I understand now what Mike meant. Being an investor is really hard work.6 [6]

Move Fast and Break Things

I was at Facebook from 2007 to 2011, and it was an incredible moment because everything was so new. Without realizing it, we were actually defining the future standards of Web 2.0 in realtime as we tried to scale the business. We even inadvertently launched Data Science as a discipline because we had a candidate with a PhD who was at Google who refused to join unless he got a job offer that said data analyst. He had a PhD in particle physics, so I said, “Great! You’re a data scientist here.” [3]

The first scaled use of machine learning was pioneered at Facebook when we introduced People You May Know (PYMK). Basically, you logged in, we grabbed your credentials, scanned your address book, did a compare, made some guesses, and presented other people you may know that weren’t already in your address book. It was actually some really basic math, but the density and entropy inside the social graph started to go crazy. PYMK really demonstrated the power of machine learning to us, and it subsequently led to the introduction of the news feed and personally tailored user content. [3]

I was head of user growth and would hold a meeting every Wednesday to review what experiments we were running to help scale the company. I asked to see them all, from the dumbest to the most impactful, and it trained people to celebrate trying instead of coming up with a supposedly correct answer. We actually didn’t see any impact from our work for months on end, but gradually, things started to accumulate. I was witnessing incremental growth in real-time, and it reminded me of Einstein's remark about compound interest being the eighth wonder of the world.7 [4]

It’s important to understand that these developments came about experimentally. As Bezos mentions, there’s a tendency after things work out to create a narrative that it was all premeditated because it feeds your ego.8 I think it's more honest to say that we were good probabilistic thinkers, and we tried to learn as quickly as possible, which entailed making as many mistakes as possible.9 [3]

‘Move Fast and Break Things’ has become a very loaded term, but you can argue it’s really just a particular movement around velocity and acquisition of knowledge. Essentially, there's a space of things we know, and a massive space of things we don't know. Now, there’s a rate of growth of the things we know, but we have to assume that the rate of growth of the things we don't know is increasing much faster. So, the most important thing is to move into the space of unknowns as quickly as possible by acquiring knowledge. In doing so, we're going to assume that a failure mode is the nominal state, so things will break, i.e. things will literally be breaking in the code, as we experiment.10 [3]

You can also argue that when a system becomes big enough, you have much less margin to experiment in an open-ended way because even small iterations could have broad societal impacts that aren’t clear upfront. For example, if you work at Boeing, and you have an implementation that gives you a 2% increase in efficiency by reshaping the wing, there needs to be a methodical ‘Move Slow, Be Right’ process. When mistakes compound in a system that’s already implemented at scale, they have huge externalities that are impossible to measure until after the fact. Basically, when an industry becomes critical, you have to slow down. [3]

I loved being at Facebook, but eventually, I had to decide whether to stay or leave. It would always be Zuckerberg's company, and if I wanted to have a real stamp on decisions, I would need to start my own thing. Really, it was about going back to first principles. What did I value? I valued my independence, my creativity, and I also valued winning over the long term. Despite the financial incentives to stay, I decided to bet on myself and leave. As Dave Chappelle said, “I got off the bus.”11 Facebook supported my decision, and provided me with some initial capital. I raised some more funds and started Social Capital in 2011. [4]

I got exceptionally lucky, so I have nothing to complain about. Facebook was a special place, and I helped change the world. It had its downsides, sure, but the time I worked there was magical. [1] [2]

Thinking in Bets

My training at all the different places I worked was actually the same: How do you think in bets? How do you make small bets? What should you actually measure? How do you then use what you’ve learned to make really big bets? [6]

The key is being able to adopt one of two opposing mindsets. When you’re making small bets, you want to avoid overthinking, and instead have a bias towards just making the bet. On the other hand, when you're making big bets, there is zero room for error, so the kind of analysis you want to undertake is much more rigorous. If you’re able to train your mind to know the difference between the two, you can do really well.12 [6]

This was the most important thing that I brought to my job as an investor when I started Social Capital. I had developed a very specific way of making bets, and I wanted to make sure that the organization I built was able to reflect that well. [6]

Sources

Bryant, Adam. "Chamath Palihapitiya of Social Capital on the Paradox of Ego and Humility." The New York Times, 2017. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/20/business/corner-office-chamath-palihapitiya-social-capital.html.

Palihapitiya, Chamath. "Chamath Palihapitiya Interview: Wharton Private Equity and Venture Capital Club Fireside Chat Series.” Wharton PEVC Club, 2023.

Palihapitiya, Chamath and Lex Fridman. "Chamath Palihapitiya: Money, Success, Startups, Energy, Poker & Happiness." Lex Fridman Podcast, 2022. https://lexfridman.com/chamath-palihapitiya/.

Palihapitiya, Chamath and Oren Zeev. "Fireside Chat with Chamath Palihapitiya & Oren Zeev." ICON, 2022.

Palihapitiya, Chamath and Trey Lockerbie. “ Building Berkshire 2.0 with Chamath Palihapitiya” The Investor’s Podcast, 2021. https://www.theinvestorspodcast.com/episodes/building-berkshire-2-0-w-chamath-palihapitiya/.

Palihapitiya, Chamath and Aqil Pasha. "A Fireside Chat with Chamath Palihapitiya w/Aqil Pasha." MIT VCPE Club, 2022.

This was prescient. The insurgency campaign waged by militia groups against the Sri Lankan government continued until 2009. An estimated 100,000 people were killed in the conflict.

Average household income in Canada for the year 1985 was approximately $38,456 CAD. For inflation-adjusted data up to 1995, see: CCSD - Average Income. Note that the average annual inflation rate from 1985 to 1995 was 3.35%. For inflation data, see: https://inflationcalculator.ca/.

In mathematical and engineering fields, boundary conditions are the constraints or conditions set at the boundaries of a system. They define how the system behaves at its limits and are essential for solving differential equations or analyzing physical scenarios, such as in fluid dynamics or structural analysis.

Buffett: “When Charlie and I buy stocks—which we think of as small portions of businesses—our analysis is very similar to that which we use in buying entire businesses.”

Lawrence A. Cunningham. The Essays of Warren Buffett (p. 135). Kindle Edition.

David Rubenstein: “I assume you get even more resumes than you get deal opportunities. How do you discern who you’re going to hire? Is there a screening process? What is the best way to get into Sequoia as an employee?”

Michael Moritz: “Hunger.”

DR: “Just be hungry? You must have a lot of people who go to Stanford Business School. You can’t hire everybody. You’re looking for people who have been entrepreneurs themselves? People who have been operating executives? People who are unusual, maybe they’re quirky, but they have a different mindset about how to look at things? “

MM: “It’s all of the above. But the most important attribute isn’t any of that. It’s hunger.”

David M. Rubenstein. How To Invest (p. 316). Kindle Edition.

Marks: “In 2011, as I was putting the finishing touches on my book The Most Important Thing', I was fortunate to have one of my occasional lunches with Charlie Munger. As it ended and I got up to go, he said something about investing that I keep going back to: “It's not supposed to be easy. Anyone who finds it easy is stupid.” See: September 2015 Oak Tree Capital Memo,

The attribution to Einstein is likely apocryphal.

”The narrative fallacy, Bezos explained, was a term coined by Nassim Taleb in his 2007 book The Black Swan to describe how humans are biologically inclined to turn complex realities into soothing but oversimplified stories.” Brad Stone, The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon (Prologue). Kindle Edition.

Amy Edmondson would refer to these ‘mistakes’ as “Intelligent Failures,” because they, “provide valuable new knowledge that can help an organization leap ahead of the competition and ensure its future growth.” See: https://hbr.org/2011/04/strategies-for-learning-from-failure

In engineering, "failure mode" describes the manner in which a system or component can fail. "Failure Mode and Effects Analysis" (FMEA) utilizes this concept to pinpoint and mitigate potential points of failure in a design or process.

Chamath’s farewell note can be found online. See: Farewell Facebook.

This calls to mind Jeff Bezos’ distinction between Type 1 (irreversible) and Type 2 (reversible) decisions; albeit, the risk of permanent capital loss is equivalent and irreversible in Chamath’s framework. See: ‘Invention Machine’ in Bezos’ 2015 Amazon Annual Shareholder Letter.